Scorpion (1985), The Human Factor (1978) and Kittler, and the Media (2013) are all novels that center around the genre of spy thrillers, a truly evergreen genre of fiction. Another commonality they all share is that they are descendants of what many historians cite as the first spy novel, The Riddle of the Sands (1903) by Robert Erskine Childers.

It is safe bet that most people today are not familiar with the name Erskine Childers. But the one novel he wrote casts a very long shadow, both in the fiction that owes a debt to it and in the impact it had in the real world at the time. Why did Childers’ work of fiction lead to so much interest from British Foreign Office?

Early Lessons in Alliances

After the untimely passing of his parents when he was a little child, Childers relocated from London to Glendalough in County Wicklow, Ireland. He grew up under the influence of the Barton family, ardent unionists who took their allegiances seriously.

According to rumors, the family had a falling out with the politically powerful and influential Parnell family, whom they considered to be traitors to the unionist cause. His proximity to this clash with the Parnells had a significant impact on how Childers developed his sense of loyalty and patriotism, although the lessons he learned led to unexpected outcomes.

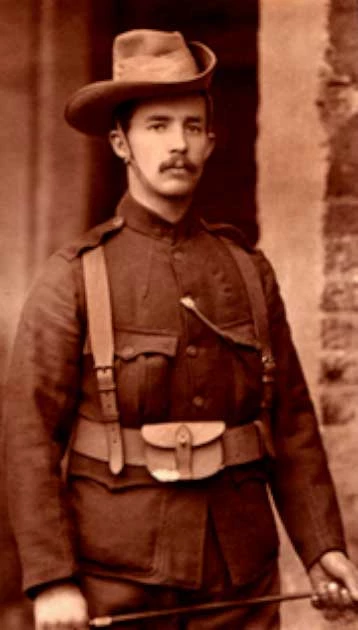

Childers nevertheless grew up as a child of the Empire, and served in the British Army in the South African War, popularly known as the Boer War. After returning Childers assumed the position of clerk at the House of Commons in London from 1895 to 1910, following in the footsteps of his cousin, British politician Hugh Childers.

The Riddle of the Sands and Invasion Mania

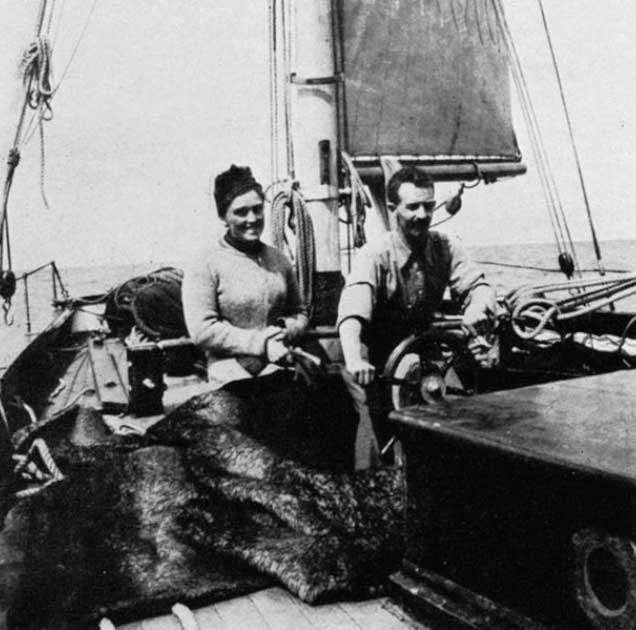

The Riddle of the Sands, Childers’s only full-length book, was published in 1903 and chronicled the adventures of two men: Davies, a sailor from an eccentric sailing family, and Carruthers, a minor official in the British Foreign Office. Together, they sailed a yacht named the Dulcibella toward the Frisian Islands off the northern coast of Germany in search of a man named Dollmann, who they believed to be an English exile disguising as a German.

Traveling along the coastal canals the pair find far more than they were looking for, uncovering a fleet of German naval ships and barges, and a conspiracy to invade Great Britain. The villainous Dollmann is defeated, the invasion thwarted and Britain saved.

This book’s release at the turn of the century, when Germany was rapidly becoming a major force in Europe, was a plausible theory, and the Foreign Office hauled Childers in to explain how he knew so much about German naval activity. It seemed that his fanciful story had struck a nerve in the corridors of power.

- Sending a Message: What was MI6 Doing With All That Semen?

- The Lusitania and the Blame Game: A Legitimate Target?

The assertion that the book was a work of fiction was not entirely convincing, given that Childers had acknowledged that one of the main characters was based on him and his own expedition across the Baltic Sea in 1897, which had taken him near the Frisian coast. His argument was not helped by the fact that his logbook entries from the novel were almost verbatim copies of his original records from 1897, even containing some unaltered passages.

But, plausible or not, the novel was out there and the public reaction was immediate. The Riddle of the Sands incited what was called “invasion mania” amongst the British public. The Foreign Office, initially not thrilled by this public airing of their secret fears, came to appreciate the novel as it became something of the wake-up call for British defense.

In a postscript release by Childers in 1903 he claimed, “It so happens that while this book was in the press a number of measures have been taken by the Government to counteract some of the very weaknesses and dangers which are alluded to above.” Of course, he worked at the Foreign Office and so perhaps knew of these dangers: could this wake-up call have been somewhat deliberate?

Did The Riddle of the Sands predict the future?

According to what Childers himself said, his book was written as “… a story with a purpose…. a patriot’s natural sense of duty”. Whether that was true or not, he was in reality emphasizing how weak the British defenses were in the face of the seemingly unyielding German forces.

In later years Winston Churchill recognized the influence of Childers writing as he acknowledged the decision to install naval bases on Britain’s north-easterly coast was down to The Riddle of the Sands. And of course we know now that Germany never invaded Britain with barges of troops, but it seems preparedness for such an attack should not be underestimated.

Childers wrote volumes on military politics, planning, and reconnaissance in the years that followed. All of these (including The Riddle of the Sands) are widely credited with emboldening a genre of “secret reconnaissance”, as Jessica Meacham notes on the genre it is a “widely accepted narrative that links the development of the modern-day MI5 with…the work of ‘invasion novelists’”.

From “Great Patriot” to “Murderous Renegade”

But, for all the impact his novel had, this is only the first chapter in Childers’s eventful life, and later things turned decidedly darker. How did a man who Churchill once called a “great patriot and statesman” become a “murderous renegade”?

In 1914 Childers and a friend (and British Army officer) ran guns by sailing from Germany, through the English Channel to Howth, on the eastern Irish coast. Childers offered the Irish Volunteers the firearms because he disagreed with British policies in Ireland, instead backing an Irish Free State and Home Rule. It seems that the Parnells had been more influential than his adoptive unionist family.

- The Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane: The First Cruise Missile?

- Wartime Sabotage in a Neutral Country? The Black Tom Explosion

However, for a time he was immune to criticism, and even after he wrote books criticizing British rule in South Africa and Ireland and sold munitions to Irish nationalists, he was still regarded as a valuable asset. Both of these actions weren’t well-known, but they weren’t kept a secret either.

Childers was valuable since he had identified Britain’s defensive flaws, so when World War I broke out, he was called upon. The British Admiralty called the Irish Revolutionary Headquarters in Dublin, where Childers was residing, requesting him to return to London and join the navy.

After the war, Childers plunged deeper into Irish politics and in 1921 was elected to the Irish Assembly as a deputy for County Wicklow, and the Minister for Propaganda. During the Anglo-Irish Treaty talks between Ireland and Britain that same year, Childers was selected to serve as the Irish party’s secretary.

This was the real moment where the tides turned for him. Childers, once strongly aligned to the protection of Great Britain, now had jumped ship opposing the group he once fought for.

The Sands Finally Shift for Childers

The two dominant factions in Ireland, Sinn Fein (Ireland’s ruling political party) and the IRA (the Irish Republican Army leading the republican movement) both vehemently opposed certain of the Treaty’s provisions, as proposed by Britain. Inevitably civil war broke out in 1922. When the National Army uncovered that Childers was creating propaganda for the republican movement, they went looking for him.

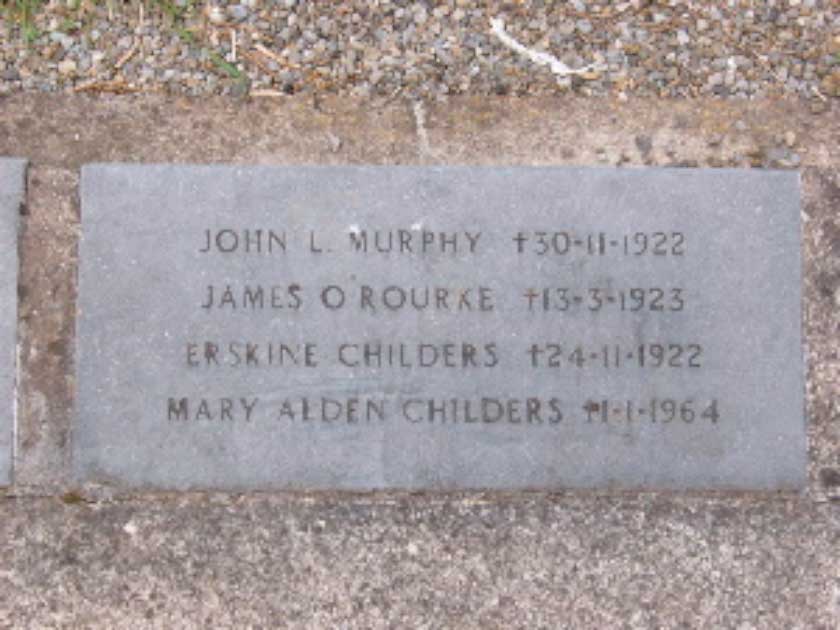

On 20th November 1922 Childers was sentenced to death by firing squad after being found in the possession of an unlicensed firearm, a capital offense. When Churchill received news of the execution, he announced that “No man has done more harm or shown more genuine malice or endeavored to bring a greater curse upon the common people of Ireland than this strange being, actuated by a deadly and malignant hatred for the land of his birth”.

It’s only in this death that the context of Childers pivotal novel, The Riddle of the Sands becomes a story of intrigue. His portrayal of himself as the noble Carruthers, a man immersed in the honor of serving his country, contrasts with the figure Dollmann who had abandoned dignity and nation.

Could the overarching plot line of shifting sands, and shifting alliances have been a forbearing of his true devotions?

Top Image: What was it about The Riddle of the Sands that concerned the Foreign Office so deeply? Source: Mikefoto58 / Adobe Stock.

By Roisin Everard