On July 28, 1996, two young men discovered a human skull in the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington state. The men called the police, who surmised that what they saw was not the scene of a crime. Thus, the officers brought in the local coroner. However, after his initial examination, the coroner was puzzled. The skull did not look like a modern one, so he sent for James Chatters, a local archaeologist. Little did Chatters know on that first day of his investigation that he was looking at the ancient remains of a human who would become known as the Kennewick Man. Nor did he know at the time that the skeleton he was looking would generate two decades of legal battles to reclaim it.

By the evening on the day of the discovery, the coroner and Chatters discovered many other bones nearby. They carefully collected them and moved them to Chatters’ office where they placed them on a table in a nearby laboratory. Chatters was pretty sure that the Kennewick Man’s skull was not that of a Native American. Over the course of the following month, they discovered more than 300 bones that made up approximately 90% of an adult human male. The teeth indicated a diet untypical of other ancient remains found in the area. Chatters investigated further. He would uncover several broken bones and a spearhead made of stone lodged in the hip of the skeleton. Clearly, this ancient man had lived an epic life.

As is common with finds such as this, Chatters sent a bone to a lab that did carbon dating. He was stunned by the results. The skeleton appeared to be approximately 9,000 years old.

Had the story stopped there, the scientists may have investigated the skeleton and then shipped it off to be displayed in a local museum. But there was a snag. Who “owned” the skeleton and had the right to decide its ultimate fate?

Claiming the Kennewick Man

Because the discovery of the Kennewick Man occurred on Federal lands, the Army Corps of Engineers, who oversaw the management of that part of the Columbia River, was first to claim control. They stated that there would be no further scientific study of the remains. Quickly, the county coroner who had assisted Chatters in gathering the bones claimed that, as the local official, he had the right to choose the future of the skeleton.

Related: Ancient Tattoos of Ötzi and the El Morro Man

Very quickly, the local Native American tribes claimed the right to take control of the remains, as stated in the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. The tribes said they would bury the remains, as was their custom, and they would cease all scientific investigations.

By this time Chatters had involved several other scientists in the study of the bones, and he desperately wanted to continue what could easily be a significant landmark in the study of early American history. To add weight to his claim, Chatters sought the help of anthropologist Douglas Owsley of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Together, Chatters and Owsley would fight for the ability to analyze and study the skeleton. In the coming years, a heated court battle ensued.

Until the courts reached a firm verdict, the Army Corps took possession of the bones and locked them away in a laboratory.

Injunction Halts Actions

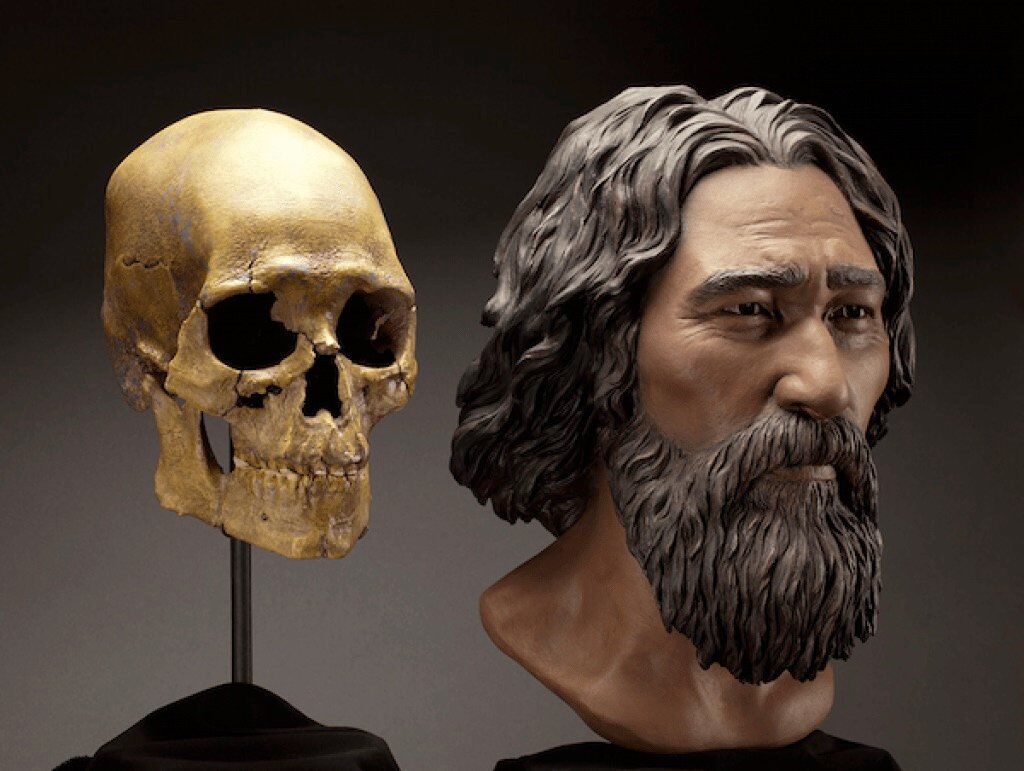

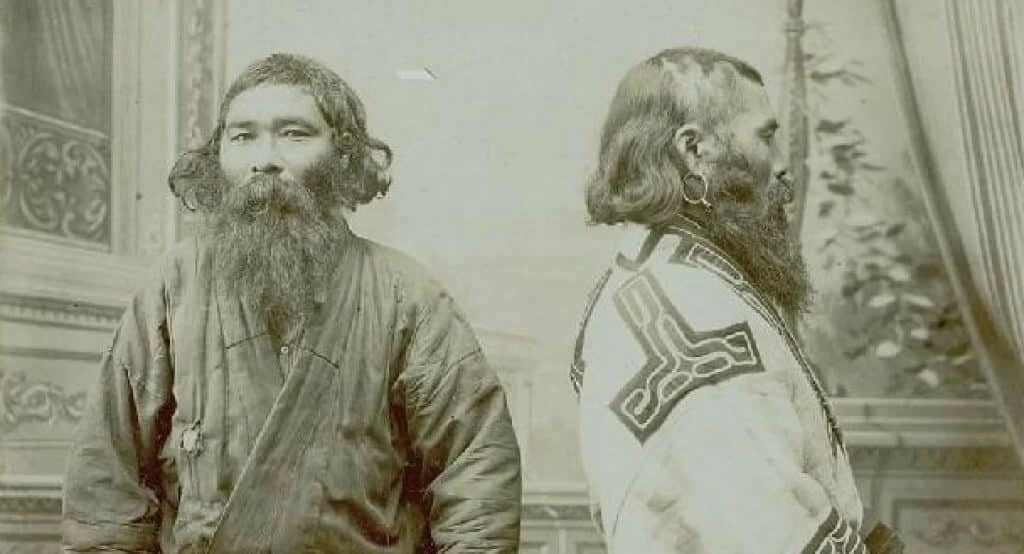

Native Americans had a strong case if they could prove that the “Ancient One,” as they called him, was, in fact, their ancestor. But the scientists didn’t agree. They claimed that the remains had much more in common with known ancestors of Polynesia, islands around New Zealand, or the Ainu people of Japan. With this information, the scientists enlisted the help of an attorney in the hopes of getting an injunction to halt any further action on the part of the Army Corps or the tribes. At the very last minute, a judge decided to hold off on any further action until experts could make a more clear assessment about the ownership of the skeleton. Meanwhile, the remains stayed in the possession of the Army Corps.

The legal case continued. Subsequently, the Army Corps moved Kennewick Man to non-public rooms in the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington in Seattle. Owsley and Chatters kept track of the bones. They protested that the Burke Museum did not have the facilities to keep the remains in the climate-controlled environment necessary to prevent further degradation of the bones. However, the museum disagreed.

In the transition to the Burke Museum, two leg bones vanished. Owsley and Chatters demanded an official investigation only to become the main suspects. The femurs would eventually be mysteriously discovered among the skeletal remains housed in the county coroner’s office.

Scientific Research Continues

The legal battle continued until a court decided in 2002 that the team of scientists could thoroughly examine the skeleton. Many people expressed shock at the decision that went against the Native American tribes and the Army Corps. The court said in part, “Kennewick Man’s remains are so old and the information about his era is so limited [that we cannot] conclude reasonably that Kennewick Man shares…genetic or cultural features with presently existing…people or cultures.” Throughout this time, the skeleton remained at the Burke Museum.

The scientists lost no time in resuming their analysis of the bones. Although they attempted to extract DNA, they were unsuccessful (Rasmussen et al. 2015). Therefore, they hypothesized that Kennewick Man appeared related to the Ainu and Polynesians mostly based on the anatomy and shape of his skull. Additionally, studies revealed many theories about how he lived and intriguing facts about his life. It appeared that he primarily ate fish and other aquatic wildlife. Signs of arthritis had set in his joints, and there were two non-fatal wounds on his skull. The scientists also determined that he may have spent periods of time in the region of Alaska. Additionally, they reasoned that other people had buried him at the Columbia River and that he did not die naturally at the site.

In 2014, the scientists produced the book, Kennewick Man: The Scientific Investigation of an Ancient American Skeleton. In the book, they discuss the findings of their years of research. But they also admitted that many mysteries remain unsolved.

A Final Determination

In 2015, an international team, Rasmussen et al., conducted a successful DNA analysis on the skeletal remains. All speculation ceased when the team announced, “We find that Kennewick Man is closer to modern Native Americans than to any other population worldwide.”

Multiple scientists verified the results, and there was no question of the validity of the conclusion.

The Army Corps of Engineers declared once and for all that they would repatriate the bones to the five Native American tribes who fought to reclaim the Ancient One.

In early 2017, the Yakama Nation, Nez Perce Tribe, Umatilla, Wanapum Band of Indians, and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation took the Kennewick Man back to the land near the Columbia River. They conducted their tribal ceremonies to grant him a peaceful afterlife. And after their 20-year fight to give him the honor that they felt he deserved, they laid him to his final rest.

*Article was updated by HM staff on May 17, 2017.

Sources:

Sites retrieved January 12, 2015:

Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture

National Geographic

Smithsonian Magazine

Sites retrieved May 17, 2017:

Smithsonian Magazine

Nature