Mary Baker (11 November 1792 to 24 December 1864) was a simple servant. But for a few months in 1817, she pretended to be Princess Caraboo of Javasu, who was kidnapped by pirates. Everyone in town believed her.

How it Started

A humble cobbler near Bristol, England, found a disoriented young woman on April 3, 1817. She was walking erratically on the road. Her clothes were dirty but unusually exotic, and she sported a turban wrapped around her head. The cobbler asked the strange woman if she needed assistance, but she responded in an unfamiliar language the cobbler could not understand. Nobody knew who this woman was, but they would quickly grow to know her as Princess Caraboo.

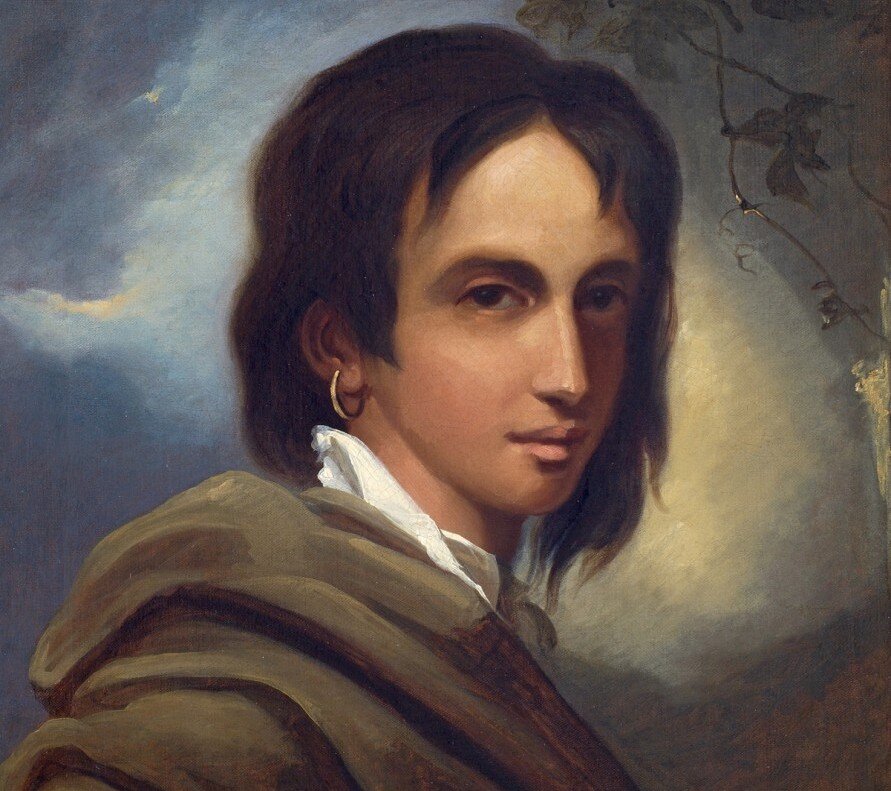

Princess Caraboo of Javasu portrait by Thomas Barker. Photo credit: The Holburne Museum

Not knowing what to do with her, the cobbler took her to the nearby Overseer of the Poor, Samuel Worrall. Worrall didn’t know what to make of her either. The sole comprehensive thing the young woman did was to point at a picture of a pineapple and say “ananas” which is the word for pineapple in several languages. With this limited vocabulary, they were not able to make out any details about the identity of the woman. They did, however, eventually learn that her name was Caraboo.

Attempts to Communicate

For lack of a better option, Worrall turned her over to the authorities who put her in prison. During her time there, Manuel Eynesso, a Portuguese Portuguese sailor said that he understood her language and that he could translate it. And indeed, he relayed her dramatic story to the authorities. He stated:

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Manuel Eynesso,”]”I think her name is not Caraboo, as stated in the newspapers, but rather that that is her country. I consider that she comes from the Bay of Karabouh, on the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea, and situated in Independent Tartary. She may easily have come from thence by the Persian Gulf, or still more easily by the Black Sea.”[/blockquote]

He added that she was the daughter of a high ranking Chinese person and a Maudin (Malay woman) that was killed in a war between the Boogoos (Cannibals) and the Maudins (Malays.). While walking in her garden at Javasu, she was seized by pirates, commanded by a man of the name of Chee-min, and carried off.

Caraboo claimed to be a princess from a small island in the Indian Ocean. Pirates had captured Princess Caraboo and took her on a long voyage. When they got to the Bristol Channel she bravely jumped ship and swam to the English shore.

Princess Caraboo Identity Revealed

The authorities quickly removed Princess Caraboo from the prison and took her back to the Worrall home. Mrs. Worrall took charge of the young princess and immediately showed her off to the local gentry. This was a big boost to the Worrall’s ranking among the area’s elite.

A Henry Meyer engraving of the imposter. Image: Public Domain.

Princess Caraboo had odd habits for 19th century England. She was skilled at archery, knew how to fence, swam naked in nearby lakes, prayed to “Allah Tallah” with one hand covering her eyes, and only used cups and plates she washed. She also had portraits made, and this would be her undoing.

Anna Anderson: Imposter of Duchess Anastasia

When one of her portraits appeared in a local newspaper, a woman easily identified Princess Caraboo as Mary Baker (née Willcocks), a young Devonshire woman who worked as a servant at several homes in the area. Mrs. Worrall found it hard to believe she had been duped. Princess Caraboo was a complete fraud.

One puzzling question is how the Portuguese sailor understood her gibberish?

End of the Charade

Embarrassed, Mrs. Worrall, confronted Mary Baker, who suddenly had no problem speaking English. Mary, who is not a Princess, but the daughter of a cobbler, created the ruse in the belief it would make her life more interesting.

Mrs. Worrall shipped Princess Caraboo off to Philadelphia in June of 1817. She tried to continue her royal identity, but nobody bought it. In 1821 she returned to England and, as far as we know, never attempted her impersonation again. Princess Caraboo eventually worked in the very un-royal occupation of selling leeches to hospitals. As Mary Baker once again, she married in 1828 and gave birth to a daughter the following year.

Mary died at the end of 1864 and buried in an unmarked grave.