The Great Glen Fault is a significant geological feature that covers the Southwest to the Northeast across the Scottish Mainland running from Fort William to Inverness, in an almost straight line. The gap eroded along the path is covered by many lochs, which were connected in the 19th century by Thomas Telford, who created a short series of waterways to make the Caledonian Canal.

At the time, it cost around £900,000 which in today’s money would be around £70 million. The trough itself is around one kilometer (0.6 miles) long whilst the flanks rise up to over 700 meters (2,300 feet) on either side.

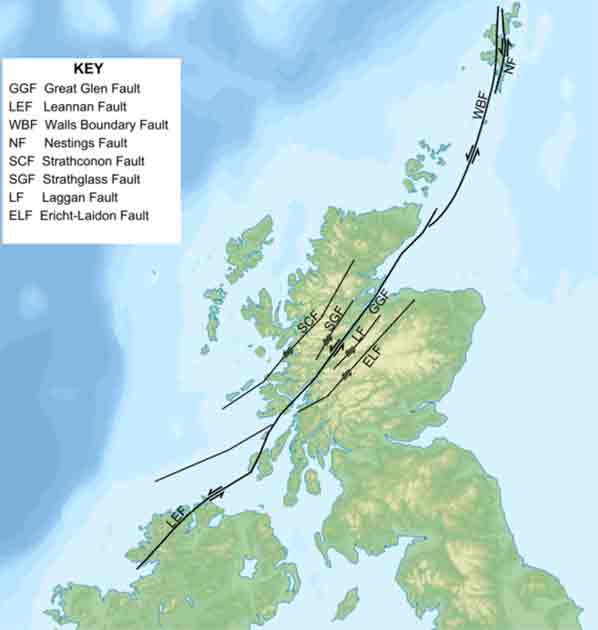

It is also continued offshore from the fault, and it is this that makes the fault so contentious, and so interesting. It is assumed that the fault’s offshore continuations control the western coast of the Moray Firth and continue to head northeast close to the Caithness coast. Some researchers have suggested that there is a link with the other nearest boundary, the Walls Boundary Fault, that runs through the Shetlands.

Research conducted in the 1980s through electrical resistivity testing indicates that the structure is a very deep one and that it extends at least 60 kilometers (37 miles) down, all the way to the base of the Earth’s crust. It is for this reason that Scotland, particularly in the highlands, experiences earthquakes now and again: there is a line that bisects the entire country, a line where the Earth is split open.

Academic History of the Fault

One of the earliest commentators of the fault came from Hugh Miller in 1841 and was described as a “foot track” that had been hollowed by the frequent tread of earthquakes. This indicates that there was at least some knowledge of the relationship between the fault line and the geological makeup of Scotland.

This line had in fact been seen even earlier, on a very basic map by MacCulloch in 1836. The earliest and most accurate description of the fault would only come decades later, in 1861 by Muchison and Geikie. They claimed that the fault appeared to be a fracture without a throw formed by preferential erosion along a line of broken and crushed rock.

- The Phantom Canoe of Lake Tarawera: The Volcanic Warning

- King Uzziah’s Earthquake: Evidence from Archaeology

Geologists over the last 100 years have been fascinated by the fault. As early as 1914, there were geological surveys taking place. In 1914, Horne and Hinxman claimed that there was a mismatch between the two sides of the fault of around 1,800 m (6,000 feet) whilst Cunningham Craig noted that there was a presence of horizontal slickensides which also indicated lateral displacement.

Shand in 1951 and Parson in 1979 authored papers that cast doubt on what stands currently as the accepted theory of a strike-slip fault. Neither of them was able to discover direct evidence for transcurrent movement in the field. Bailiey in 1916 and his team drew attention to the mismatched grades in the rock which could only be described by vertical or lateral movement across the fault.

In 1939, Richey analyzed Scottish Dykes and the geology of the area and was able to conclude that the Great Glen (formed along the faultline) was formed sometime between the early Devonian and late Carboniferous stage. This was further bolstered by Kennedy in 1939 and was published in 1946.

The main argument in this thesis was that there was a displacement of 104 km (64 miles) between two different granites along the fault: whatever had caused it had resulted in a serious drift of matching rock, one side to the other. He believed that this came from a single intrusion. In the following decade, a few papers continued Richley’s work across the Highland dykes.

Johnstone and Wright in 1951 were the first people to suggest that there were two separate areas of movement across the fault line whereas Leedal in the same year concluded that there were many minor movements to create the Great Glen. All were in agreement: the fault was something major, and that it effectively bisected Scotland.

There has been much more discussion on the movement history of the Great Glen Fault. However, only a consensus in these most general terms has been achieved. Despite the numerous different approaches that have been taken across many years, there are few conclusions that are the same.

Different topics and criteria have been deemed important at different times and as such there is not one single approach that has been able to give an overall simplified idea of what is going on here. More recent studies have attempted to focus on a general history of the movements experienced by the fault, but agreement remains on a few key points: the fault is unusually straight, it is ancient, and it is extremely deep by any standards.

The key main facts that have been agreed upon around the Great Glen Fault are that it was created as a wrench fault, a sudden shift during the later phases of the Caledonian period. There were likely additional minor movements and displacement that caused the fault to move in the early formation of it.

There have been many signs found of early deformation through the environment though there is not a lot of evidence surviving. It has been more difficult to find evidence of later phases of movement which may have happened.

One of the biggest issues that face research who are trying to identify the Great Glen Fault beyond mainland Scotland is that there is little trace of it. The assumption right now is that the fault runs into the Walls boundary through Shetland but there is huge doubt about this as their history and geology are markedly different.

The Great Glen Boundary Today

There has been present-day seismic activity along the Great Glen Fault as recently as 2021. There has been approximately a dozen recorded earthquakes since the largest one identified in Scotland which reached a magnitude of 5.1 near Inverness in 1816.

An interesting natural phenomenon that has continued to pique the interests of academics and tourists alike is the release of bubbles within Loch Ness. Loch Ness is one of the Lochs that runs along the Faultline, and some research suggests that seismic activity along the faultline releases bubbles from the bed of Loch Ness so that they are visible on the surface.

It is perhaps these bubbles that have contributed to the myth of the Loch Ness Monster and allowed the stories to survive to the modern day. This is certainly no less believable than the other theories that survive around the monster and its existence though many of the believers would doubt this heavily.

Regardless of the truth of the matter, the Great Glen Faultline is one of the major Faults that crosses Scotland and is so large that it is visible from space. And with so little still understood about it, who knows what it will do next.

Top Image: The Great Glen Fault can easily be seen from space, marked by a line of deep lochs. Source: NASA / Public Domain.

By Kurt Readman