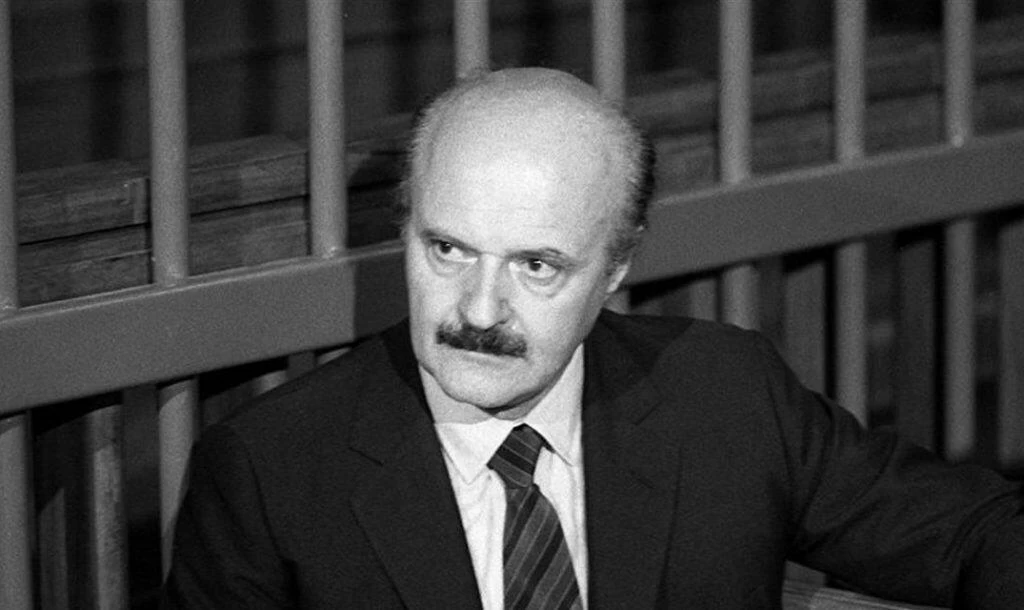

London is a typical metropolitan city just like many others around the world. Just like many others around the world, the allure of the so-called ‘bright lights, big city’ can trap the unwary or naive in its more sinister underbelly. This is most often true for young adults that can be drawn in by the possibility of a better life, only to discover that the end of their life is waiting for them. Roberto Calvi, the 62-year-old chairman of an Italian bank, would not normally be vulnerable to a situation like this. However, in 1981, the powerful banker found himself caught in the midst of a financial scandal that would lead to one of London’s most controversial unsolved deaths.

Banco Ambrosiano’s Illegal Export of Millions

During 1978, the central bank of Italy (BoI) published a report about the activities of Italy’s second-largest private bank, Banco Ambrosiano, from which billions of lire ($27 million) had been transferred out of the country illegally. This led to a full-fledged criminal investigation resulting in the conviction of the chairman of Banco Ambrosiano, Roberto Calvi (nicknamed God’s Banker) in 1981

Ultimately, he received a four-year suspended sentence and a fine of nearly $20 million for his part in moving the equivalent of $27 million out of Italy. Rumors circulated that he made at least one attempt at suicide while he was in jail. Despite his imprisonment, Calvi managed to keep his position at the bank and was eventually granted bail, pending the appeal. Members of his family believed that he did not willingly do the things that he was accused of. They believed, instead, that someone maneuvered him into it, while others insisted outright that he was completely innocent.

The Holy See Involvement

The following year, the Banco Ambrosiano collapsed, but two weeks prior to that, Calvi authored a letter to Pope John Paul II. Calvi stated that the collapse would have the most profound impact on the Church and prove to be something of a financial catastrophe overall. Without going on record to confirm matters, the letter heavily implied that officials within both Ambrosiano and the Vatican were aware of what was really going on. The Vatican was the largest shareholder of Ambrosiano, and in the lead up to the collapse of the bank, debts of up to $1.5 billion were discovered. This included debts to the mafia. In 1984, the Vatican Bank agreed to pay off 120 of the Ambrosiano creditors $225 million. However, due to a lack of evidence, the Vatican Bank received immunity.

Calvi Escapes to London

On the 10th of June 1982, five days after contacting the Pope, Calvi disappeared from the apartment he had in Rome. Using a false passport, he managed to fly to London with a single stopover in Zurich. One week after his absence was noticed, officials at the Bank of Italy relieved him of his post there. Calvi’s private secretary, 55-year-old Graziella Corrocher, wrote a note that condemned the damage Calvi had done to the bank and the majority of the staff employed there. Corrocher then died when it appeared that she threw herself from the bank’s fifth-floor window. Investigators ruled her death a suicide.

The Mysterious Death of Roberto Calvi

The following night, Calvi left his flat in the Chelsea district of London for a meal. When he had finished his supper, he decided to take a stroll along the north bank of the Thames. What happened after this has been hotly debated for over three decades. Roberto Calvi was discovered in the early hours of June 18 suspended beneath Blackfriars Bridge close to the financial heart of London. He had approximately $15,000 in cash that consisted of three different currencies. Also found on the body were some bricks inside his clothing.

News of the discovery of his body sent shockwaves throughout the city. It didn’t take investigators that long to identify the corpse as that of Roberto Calvi. The investigation lasted for a little over a month before a final determination. Officially, the cause of death was suicide.

Almost immediately there was doubt surrounding this conclusion. Members of Calvi’s immediate family did not accept that he took his own life and hired George Carman as legal counsel. The original verdict was challenged and a more thorough private investigation began.

Private Investigation Brings New Theories

In 1991, Calvi’s family hired a private detective by the name of Jeff Katz, who in turn had a number of forensic tests performed on Calvi and the items he was wearing at the time of his death. Investigators found several bricks in his suit pockets and underwear. However, tests of Calvi’s hands indicated that there was no trace of brick residue. It appeared unlikely that Calvi’s hands ever touched the bricks, which meant someone else had placed them there. There were also injuries on Calvi’s neck, but these were not consistent with a hanging death. Additionally, Calvi’s shoes had no traces of rust or paint present on the scaffolding of the bridge.

You May Also Like: Mysterious Death of Natalie Wood

Katz’s investigation turned to the possibility that the killers staged Calvi’s death to look like suicide. Tide reports of the Thames river indicated that the water level was high enough to enable a boat to moor beneath the bridge at the exact time of Calvi’s death. It would have been possible for someone on board to easily reach the scaffolding. It now appeared that someone hung Calvi from the bridge sometime after his death.

Was It Really Suicide?

To add even more credence to a theory of foul play, the team could not see how a man in his sixties and not in the best of health could have accomplished this suicide. He would have navigated his way beneath a well-used bridge in the middle of London, shimmied along the scaffolding, and then chosen a spot to loop one end of a rope around the scaffold and the other around his neck, all without being seen by anyone and carrying several bricks concealed beneath his clothes. One scientist went as far as placing similar blocks beneath his own clothing and recorded chaffing to his thighs. Calvi’s body did not reveal any such chaffing. A second ruling about a year after the first returned an open verdict. It was better than suicide, but still not really a definitive answer.

The Case Reopens with New Facts

In 2002, another forensic report officially established that the cause of death was murder. The City of London Police reopened the case in September 2003 as a murder inquiry. As this new investigation progressed, additional facts came to light.

Before Calvi fled Italy, he reportedly behaved as though he was in fear of his life. Among the customers of the Banco Ambrosiano was the mafia. They used Calvi’s bank as part of their money-laundering operations, and Calvi was integral to the crimes. Some people theorized that Calvi, himself, had either personally siphoned off large amounts of this money or allowed it to happen under his watch. Calvi may have also had inside-knowledge of corrupt activities of powerful Italian politicians and even the Vatican. Furthermore, Calvi supposedly had access to at least some secrets that had to remain hidden. The bank chairman was clearly in a powerful position of influence and, perhaps, he may have been one of the more dangerous people in Italy. If all of these rumors and conjecture are true, then there is a strong possibility that he knew too much.

Mafia Ties

Some people claim that Calvi embezzled the mafia out of $50 million. When the bank crashed, the organization lost their money. They may have held Calvi culpable and decided to make an example out of him. Perhaps when he left Italy the mafia tracked him every step of the way. Calvi did use a fake passport to get to London, but the identity he used, Gian Roberto Calvini, was not far off his own true name.

Additionally, when Calvi reached London, a local drug dealer, Sergio Vaccari, and another businessman from Sardinia, Flavio Carboni, assisted him. Both had mafia ties. At the time, Vaccari was living in Kensington and considered himself something of a playboy character. He owned an antique dealership which he ran with his girlfriend.

Sometime during 1981, before the scandal broke, Vaccari had returned to his native Italy where he allegedly met with a mafia boss in Sicily. If Calvi was the victim of foul play, then Vaccari was a good candidate as a suspect. Three months after Calvi was discovered, Vaccari was found at home with 15 stab wounds to his face and neck. Even though Vaccari also had bricks in his pockets, police did not link the deaths at all. Officers also found a document containing a list of the members of the secret society, Propaganda Due (P2), in his apartment.

P2 Secret Society Ties

Calvi was a member of the illegal P2 Masonic lodge. Members of the group refer to themselves as frati neri, which translates into ‘black friars’. Thus, it seems an odd coincidence that the killers used Blackfriars Bridge from which to hang Calvi. Although it is strictly conjecture, another strange coincidence was the bricks in the pockets of Calvi and Vaccari – a possible symbolic warning by the P2 Freemasons.

Propaganda Due was originally a Masonic lodge that began operating at the end of the Second World War. However, in 1976 its leaders withdrew the Masonic constitution, and P2 became involved in more sinister persuasions. One of their aims was to achieve an ultra-right-wing government. Thus, their network ran deep into many of the most powerful positions in Italy. Often described as a ‘State within a State,’ the Masonic lodge counts politicians, judges, journalists, military officers, businessmen, and other top-tier Italians among its members. Over the years, the organization had become a highly clandestine organization led by the extreme fascist Grand Master, Licio Gelli. The Constitution of Italy Article 18 banned these types of secret organizations.

Implications of Murder

Throughout the investigation, a few top-level Mafiosi testified to the organization’s involvement. More specifically, they provided information about who may have taken part in Calvi’s killing.

Finally, in July of 2003, prosecutors identified the connection between the Vatican, the mafia, and the P2 lodge. The Vatican owned the biggest share in Banco Ambrosiano. The mafia was one of the bank’s key customers, albeit one with ‘special needs.’ P2 was also a powerful customer. Calvi not only managed massive amounts of mafia and P2 money, he laundered their funds and financed the organizations through the bank. The mafia and the P2 leader, Licio Gelli, may have worked together to silence and punish Roberto Calvi when they lost their money in the bank collapse of 1982.

Five people went to trial in 2005 for the murder of Roberto Calvi. They were Francesco di Carlo and his ex-girlfriend Manuela Kleinszig, businessman Ernesto Diotallevi, mafia boss Giuseppe Caló, and Silvano Vittor, Calvi’s bodyguard. Licio Gelli never received a formal indictment. In 2007, the courts acquitted all five defendants for lack of evidence. To this day, there have been no convictions for the murder of Roberto Calvi.

You may also like: Harold Holt – Disappearance of the 17th Prime Minister of Australia

References:

The Independent

Italy On This Day

The Guardian

Daily Star