The word “nuclear” is one of the most loaded and controversial in the modern age. The sheer power of the energies involved means that what can be an almost unbelievably destructive force was, at least at its inception, seen by many as a golden opportunity.

Here was near limitless energy, which could potentially be safely harnessed and used for the betterment of mankind. Here was the future.

Nowadays of course, the first thing that springs to mind is probably nuclear weapons. The second thing that comes to mind is probably nuclear power plants, specifically the disasters such as at Chernobyl, Three Mile Island and Fukushima.

And in truth, ever since the first nuclear bombs were detonated, nuclear power has quite rightly made most people incredibly nervous. In the 1950s the United States recognized that nuclear energy was getting a lot of negative press and tried to turn things around.

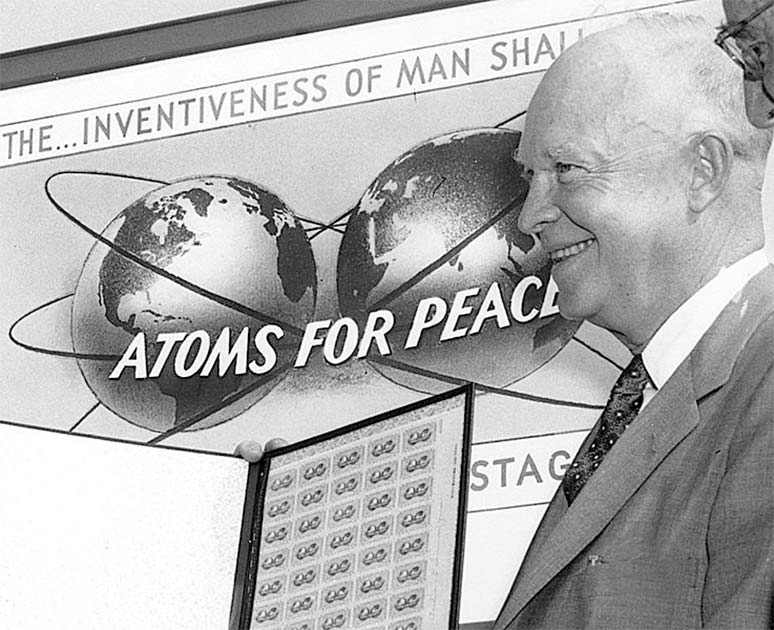

It announced the “Atoms for Peace” Initiative, an attempt to promote the good that nuclear research offered humanity if nations could just work together. While much of this research was aimed at nuclear power, some designers came up with some more “out there” uses for nuclear energy.

Like Frank Tinsley and his Atomic Airship.

The Atoms for Peace Initiative

The Atoms for Peace Initiative was an effort led by the United States to make nuclear science less scary and to focus on the potential benefits it offered mankind. It was really meant to fix a problem America itself had caused by the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, and the passing of the 1946 Atomic Energy Act.

This act reflected the US’s policy of preventing the spread of nuclear technology through secrecy and denial. Not just against the USSR, but even allies who had helped the US develop the atomic bomb in the first place.

By 1953 it was clear that this policy had failed. Despite the US’s best efforts (and thanks to the Rosenbergs), the USSR had become a nuclear power anyway and had tested its first atomic bomb. At the same time, other countries had made great strides in creating more peaceful uses for atomic power, like cleaner energy.

- Enormous, Nuclear, and Just Possibly Feasible? The Lockheed CL-1201

- Fogbank: Lost Material of the Nuclear Age

America became worried that since the information was out there anyway, attempting to keep nuclear energy secret was only going to hurt America’s global influence in the field. Rather than keeping secrets, America needed to influence the global direction of atomic research.

This new point of view was announced to the world by President Eisenhower in his “Atoms for Peace” speech, which he gave to the UN General Assembly on December 8, 1953. In this famous speech he stated that since the atomic cat was out of the bag, nations should work together to promote the positive properties of atomic research, rather than focus on the evil that could be done.

He proposed that nations already conducting nuclear research should donate some of their fissionable materials to a new agency, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). This agency, under the jurisdiction of the US (of course), would then be responsible for protecting, and handing out these materials to states carrying out peaceful nuclear research, especially nuclear power.

As Eisenhower put it, by working together the existing nuclear powers would, “be dedicating some of their strength to serve the needs rather than the fears of mankind”. Behind closed doors, the US also hoped Eisenhower’s initiative would slow down the arms development of other nations by diverting some of their limited fissionable products to the IAEA.

Exciting New Ideas

For a long time, nuclear-related research had been a closely guarded secret, but this also changed under the Atoms for Peace Initiative. Both America and the USSR began declassifying and releasing as much of their research as they could in an attempt to show off who knew the most.

By 1958 rule changes in the US meant anyone who wanted could access the basic information needed to start working on their own nuclear research. Furthermore, the US government commissioned scientists, engineers, and artists to come up with peace-themed nuclear projects.

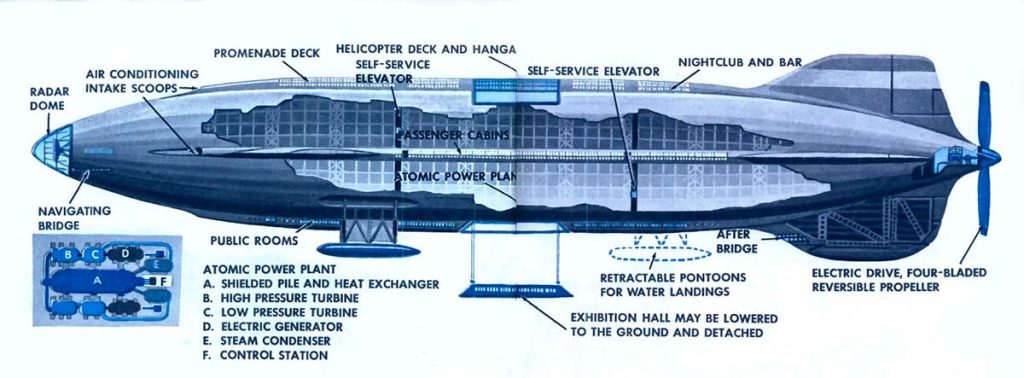

One of these was the comic-strip artist and illustrator Frank Tinsley. He began by sending his designs for a nuclear-powered airship to a hobby magazine, Mechanix Illustrated. The designs were impressive, envisioning a new kind of air transport, and soon found their way into more specialist literature.

Airship designers had always had the same problem, an engine big enough to drive an airship was also incredibly heavy and cumbersome (throwing off balance), meaning they had to install multiple smaller power plants along the length of the ship. A nuclear-powered engine promised to solve that problem.

While Tinsley’s designs were just that, designs, they did grab the attention of the US government. Congress liked the idea of a nuclear-powered airship that could travel the globe, spreading the message of peaceful nuclear energy while also showing off how advanced American nuclear technology was.

Yes, but an Atomic Airship?

So, what happened? Why don’t we have nuclear-powered freighters flying in the sky today? Well, the designs might have been impressive, but they really weren’t all that practical.

- The NS Savannah: Whatever Happened to Nuclear Powered Civilian Ships?

- Whoops! How did the US Misplace Six Nuclear Bombs?

Firstly, let’s reiterate, Frank Tinsley’s designs were just a concept. They were purely conceptual, and while innovative and imaginative, they exceeded the technological capabilities of the time.

The construction of large-scale airships involves numerous engineering challenges, such as structural integrity, propulsion, and buoyancy control. And that’s before you think about strapping on potentially dangerous nuclear reactors.

The world also hadn’t forgotten the Hindenburg disaster of 1937, where a German airship caught fire and crashed. This led to a long-term loss of confidence in airship travel, which even by the 1950s hadn’t gone away.

The Hindenburg had been bad enough. An airship with a nuclear reactor was just too scary a thought. Over time, the development of aviation and the shift towards more practical aircraft designs, such as airplanes and helicopters, led to a decline in the interest and feasibility of airship projects in general and the US government lost interest.

The Atoms for Peace Initiative had a huge influence on modern science. But it can be argued that it was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it led to many benefits, especially when it came to researching nuclear power and promoting international cooperation. It also birthed the IAEA, which exists to this day and works hard to push the contemporary nonproliferation regime.

On the other hand, it also accelerated the same nuclear proliferation it sought to curb. Just because states said they were working on peaceful nuclear projects didn’t mean they weren’t working on nuclear weapons on the side. The Initiative made nuclear knowledge more accessible, and the simple fact is nations used that knowledge to make bombs.

Designers like Frank Tinsley came up with lots of great designs for how nuclear energy could be used peacefully, but in the end, none of these dreams really came true. We don’t have nuclear-powered planes, airships, or cars.

What we do have are nuclear-powered military submarines, nuclear warheads, and a constant fear of terrorists building dirty bombs. Even with the rise of global temperatures and the fact fossil fuels are running out, nuclear energy has continued to face an uphill battle. The Atoms for Peace Initiative wanted to make atomic power less scary, but people are still afraid, perhaps now more than ever.

Top Image: Frank Tinsley’s atomic airship was one of the wilder ideas to come out of the Atoms for Peace initiative. Source: pixabay / Public Domain.