As a city’s population grows, the desire for space to build homes, businesses, schools, and houses of worship becomes more important. City expansion is normal, as history has demonstrated, but one thing often gets overlooked.

What is a city to do with its deceased residents? If space is limited and there are more bodies than space to bury them, where do the corpses go?

This was a struggle London faced in the 19th century, as well as becoming a major health crisis. Two men proposed a unique idea: develop a railway for the dead and bury them outside the city.

This strange idea grew into the London Necropolis Railway. And it operated a service for the dead for 87 years.

London’s Burial Crisis

Before the start of the 19th century, London buried its dead in and around local churches. There was very little space, and the oldest graves would regularly be exhumed to create new spots for new burials.

During the first half of the 19th century, London experienced a massive population boom that saw a city of under 1 million people in 1801 to a staggering 2.5 million by 1851. While the population grew, the space designated for graveyards remained the same.

There was, in total, around 300 acres (121 hectares) which could hold the dead, spread across 200 small locations. Due to the very limited space, decaying corpses contaminated the water supply, which caused regular outbreaks of epidemics like smallpox, measles, typhoid fever, and cholera.

A crisis point was reached when the 1848-49 cholera epidemic struck the city. 14,601 people died, and there was no burial space for the influx of corpses. Things became so bad that there were often large stacks of corpses waiting for burial, and the practice of only exhuming old graves had to be abandoned.

The cemeteries were so crowded that digging a new grave without hitting an existing grave was impossible. The piles of decaying bodies became a significant health crisis. Germ theory hadn’t been discovered and developed yet, and at this time in history, the spread of disease revolved around the miasma theory.

The miasma theory was the belief that bad smells cause illness, and piles of rotting bodies smelled terrible. Not quite right, but nevertheless something needed to be done, or London would continue to be ground zero for more deadly epidemics.

London Necropolis Railway

Sir Richard Broun, a man involved in fantastical schemes his entire life, and lawyer Richard Spyre proposed using the newly established mechanized transport (trains) to solve the burial crisis. They planned to buy a massive tract of land about 23 miles (37 m) from London in Brookwood near Woking, Surrey.

They felt that at that distance, the new cemetery would be large enough to accommodate far more than the projected population growth of London for centuries. Broun had the idea of establishing dedicated coffin trains that would carry 50-60 bodies at a time from London to the necropolis in Brookwood early in the morning and late at night.

When the coffins arrived at Brookwood, they would be stored on site until the funeral. Mourners would be transported to and from the cemetery via a passenger train during the day.

According to Broun’s calculations, a 1,500-acre (600 hectare) site could hold 5,830,500 individual burials in a single year. In an emergency “pauper” burials could be used where the dead were crowded closer together, allowing the site to hold almost thirty million dead bodies. Broun felt that this made his solution suitable for centuries to come.

Along with accommodating the newly deceased, the plan was to use the London Necropolis Railway to transport large numbers of exhumed bodies. These came from the pre-existing and overcrowded cemeteries in London, and were taken to the spacious Brookwood cemetery.

Brookwood Cemetery

Once a train reached its final destination (no pun intended), it would pull into one of two stations. The first station was designated for Anglicans, and the second station was for non-Anglicans (Nonconformists) who did not want a Church of England funeral.

Each train station car had waiting rooms explicitly designated for the dead and alive passengers. The train was separated by both religion and social class to “prevent both mourners and cadavers from different social backgrounds from mixing.”

Although Brookwood was pretty far from London, the pair argued the train’s speed (opposed to the speed of a horse-drawn carriage) made it easier and less costly than traveling to the already established magnificent seven graveyards around London. And the system operated smoothly and as planned, with the London Necropolis Railway never raising its fares for the first 85 years of its 87 years in operation.

Living passengers were charged 6 shillings for a first-class seat, 3 shillings and 6 pence for a second-class seat, and 2 shillings for a third-class seat. Today, that fare would equate to £30, £17, and £10 for a round-trip ticket.

For the deceased passengers, the fare was 1 pound for first class, 5 shillings for second class, and 2 shillings and 6 pence for third class. Today, that fare would equate to around £100, £25, and £12 per class for a one-way ticket.

As civil engineering projects like new railways, a sewer system, and what would eventually become the London Underground were being undertaken, churchyards would often be demolished, and bodies had to be exhumed. The first significant relocation of exhumed remains occurred in 1862, and approximately 7,950 bodies were taken to Brookwood. During its operation, 21 burial grounds in London were relocated to Brookwood.

A unique feature of Brookwood was that, in 1929, a portion of the grounds was turned into the Brookwood American Cemetery and Memorial. This was the only burial ground in Britain that was solely dedicated to US military casualties of WWI.

A total of 468 military men were buried in the American Section during WWI. The American Section was expanded after the US joined WWII, and new burials began in April 1942. By August of 1944, 3,600 servicemen were buried at Brookwood before it was discontinued.

Once Brookwood’s American Section closed, US soldiers were buried at the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial. Eventually, all the American remains were returned to the United States for burial on American soil.

During WWII, the London Necropolis Railway’s central station at Waterloo and the bridges near the Thames River became a major target during the blitz. On the night and early morning of April 16th and 17th, 1941, one of London’s final major air raids hit the Waterloo area.

According to reports, “rolling stock berthed in the Necropolis siding was burned, the railway arch connecting the main line to the Necropolis terminus was damaged.” By 2 PM that afternoon, an inspection was undertaken, and it was deemed that there was too much damage, and the Waterloo station was officially closed on May 11, 1941.

In September of 1945, the directors of the London Necropolis Company met to decide if they would rebuild the Waterloo terminus and resume operation. However, due to being unused since its destruction in 1941, the ground was in too poor a condition to spend the money rebuilding the line.

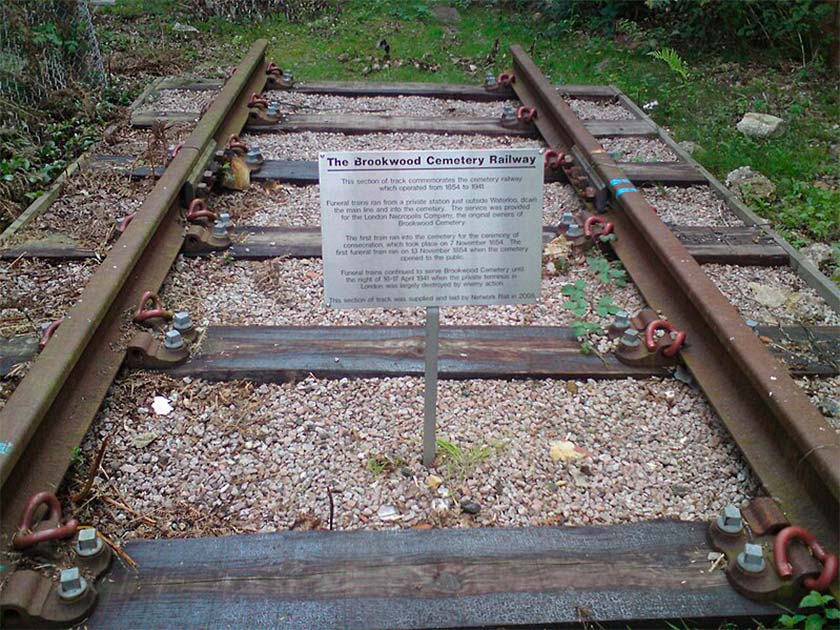

Cremation became more popular, and the demand for funerals sunk; before WWII, the train ran only twice a week on a good week. After Brookwood was essentially abandoned in the 1970s, burials resumed but never saw the millions of graves Broun and Spyre projected. A small section of the railway tracks, a memorial plaque, and a cemetery street have since been converted into a historical site.

Top Image: The London Necropolis Railway was a brilliant solution to a serious problem. Source: Timothy / Adobe Stock.

By Lauren Aguirre