The image of a Roman soldier is a familiar one to modern audiences. The high, rectangular shield, the sandals, the pilum (javelin) and the sturdy sword are all standard features of this most disciplined and fearsomely effective of fighting units.

But there was a time when the Romans were just another scrappy European civilization, distinctive because they were a republic rather than because of their military might. The Roman army, and by association the Roman Empire itself, was built on a radical modernization of the pre-existing order. This updating of the Roman fighting forces, known as the Marian Reforms, was an attempt to build a modern army essentially from scratch.

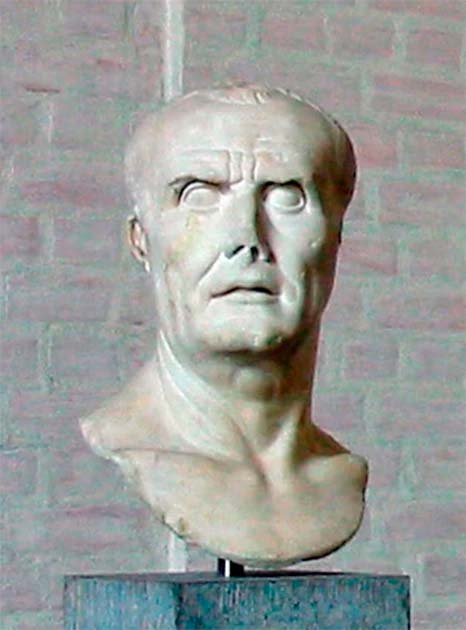

The Marian Reforms are often categorized by historians as a turning point in Ancient Roman history. They were introduced in 107 BC by Gaius Marius who humbly donated his name to the reforms. These reforms are seen as a reaction to the logistical and military stagnation of the Roman Republic.

There had been centuries of invasions across the Mediterranean by the Romans which had led to them making many enemies. By the late 2nd century BC, there were numerous invasions and uprisings across the Republic that stretched the resources of the Roman Empire. Something needed to be done.

When appointed as a Consul, Marius proposed radical alterations to the military structure of Rome and hoped to implement a more permanent, dynamic, and professional army. The reforms standardized what a legionary and cohort were and changed the barriers to the entrance to the Roman army so that more people could be recruited.

One of the most important things he did was put the logistical management of supplying and running an army into the hands of the commanding general. This change, and the enormous increase in authority it gave to the generals, allowed Julius Caesar to seize the power of Rome half a century later.

But how did Marius do this? And why did Rome have to change?

Pre-Reform

The armies of Rome before the reform in the 2nd century BC were made of a conscript levy of all male citizens. When an army was required, the consuls would select their army through drawing lots, called “dilectus”.

- The Vanished Legion: What Happened to the Roman IXth?

- The Lost Army of Cambyses: 50,000 Men Swallowed by the Desert

This was the duty of every man who was physically able to serve whenever a campaign was called. Once called up, the men would go through extensive training and be organized into four legions. The experience was gained on a campaign but as this was an annual call-up, all the experience that an army had was lost when it disbanded at the end of the fighting.

Garrisons in other territories such as Macedonia and Hispania were disbanded when the commander decided. The pay was not good, and they were often not paid on time at all by the state. This encouraged looting and plunder from any state’s victim to the Roman army.

To be a male citizen and become a member of the Roman army, you had to own enough property and be of a certain value. To join the army, Romans had to be of the 5th census class or higher. This was the class that paid taxes and earned enough money to bring their weapons.

Weapons and armor were not provided by the state and Romans were expected to own and maintain their own. Men were only called up if they were worth around 3,500 sesterces in value.

This narrowed down the pool of potential soldiers that Rome could recruit. It created a significant problem when the Roman Empire continued to expand.

It expanded at an explosive rate and thus the campaigns became longer lasting, sometimes running for years and years. It could lead to financial ruin for the less well-off Roman citizens when they were not paid on time or did not get the plunder required.

The Marian Reforms

The military system of Ancient Rome was not sustainable, and it was clear to everyone, particularly Marius. The final straw for him was when he was appointed the task of concluding the war with Jugurtha, king of Numidia in Africa.

By the time Marius was appointed Consul the campaign had stretched on for 2 years without a decisive win. Moreover, when he was appointed to this task, he had no army. The army that had been there was given to a more senior consul who was fighting elsewhere. Some men would fight, but none were of the right class and thus Marius was faced with the threat of defeat, and disgrace.

One of the first reforms that Marius introduced was the inclusion of those Roman citizens who did not own land. They were unknown as the “capite censi”. These were men who could not be assessed by the census because they had no property.

- Alesia! The Lost Battle and the Roman Conquest of Gaul

- The Etruscans: Who Lived in Italy before the Romans?

As these men were from poorer classes of society, they could not afford to bring their weapons and armor. Marius organized for the state to supply them and through this gesture offered a way for those who were of the lower classes to own money and renown as professional soldiers.

In response to this new arrangement, the people flocked to Marius. People were enlisted for 16 year periods (effectively a tour lasting their entire fighting life) and thus Marius massively increased the resources of the Roman army.

In addition to this, Marius also introduced a standing army. He wanted to get rid of the way that an army would disband at the end of every campaign. By creating career soldiers, he ensured that his men were well-experienced, well-trained, and well-equipped. The men were trained year-round even during peaceful times and became familiar with their equipment.

Marius introduced cohorts to the Roman army which took over from the previous system of maniples which was 120 soldiers over 3 ranks. Cohorts were instead 480 men divided into 6 centuries of 80 men which were further divided into 10 contubernia who all shared a tent.

10 cohorts made up a legion. This new arrangement, along with the permanent standing army, bonded the soldiers and allowed them to become familiar with each other. This is turn improved their fighting ability as a unit.

Finally, Marius offered retirement benefits that came in the form of land grants and citizenships if soldiers came from Roman allies rather than the home territories. Land grants were a great way to motivate the less economically well-off troops. It was a chance for them to make a legacy for their family.

An Instant Impact

There was a huge increase in military capability in the Roman army after these changes. An army no longer had to be cobbled together and hastily recruited from novice soldiers. There was a standing army ready to go.

And the army did go, rapidly expanding the Roman Empire and gaining the formidable reputation that they have today as a war machine. However, there were downsides to the new, military culture Marius had introduced.

The loyalty of these soldiers shifted over time from the distant, shifting state to the generals who led them to victory. Soldiers depended on their generals to lead them to glory and riches.

It was this kind of loyalty that led to the civil war and the end of the Republic. The Marian reforms were so effective that they turned the Romans on themselves.

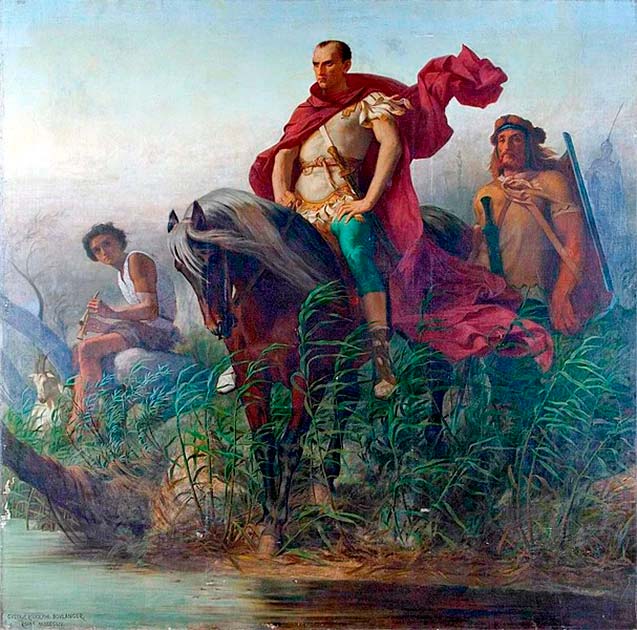

Top Image: A Roman cohort, trained to fight as a unit and an effectively military force after the Marian Reforms. Source: Lunstream / Adobe Stock.

By Kurt Readman