The classic absinthe is one of the most, shall we say, ornate drinks you can order at a bar. The shapely reservoir glass makes the small amount of green liquid glow in the bar’s lights.

Before you can meet the green fairy, a sugar cube is placed on top of an ornate spoon, and the glass is set under the tap of an “absinthe fountain,” which gently drips ice water over the sugar. Or perhaps you are served absinthe with the Bohemian Method. The sugar cube is set on fire, dropped into the spirit below, and quenched with a shot of cold water.

Once the wickedly green liquid turns cloudy and develops its opalescent louche, the drink is ready, and the green fairy waits for you at the bottom of the glass. With its rumors of causing hallucinations or inspiring great creativity, you dive in and excitedly wait to feel the effects.

You wait but are disappointed to discover that nothing has happened to you, and it’s confusing. Isn’t absinthe known for causing hallucinations and was so powerful it was illegal across the globe? Does absinthe do anything to you?

Absinthe

Absinthe is a naturally green-colored anise-flavored spirit derived from several plants, including the flowers and leaves of Artemisia absinthium (“grand wormwood”), along with green anise, sweet fennel, and other medicinal and culinary herbs.” Absinthe is a strong alcoholic spirit that ranges between 45-574% ABV or 90-148 proof US.

While absinthe is usually green, it can be colorless, red, black, or blue. While the spirit has a high alcohol content, absinthe is usually diluted with water before consumption.

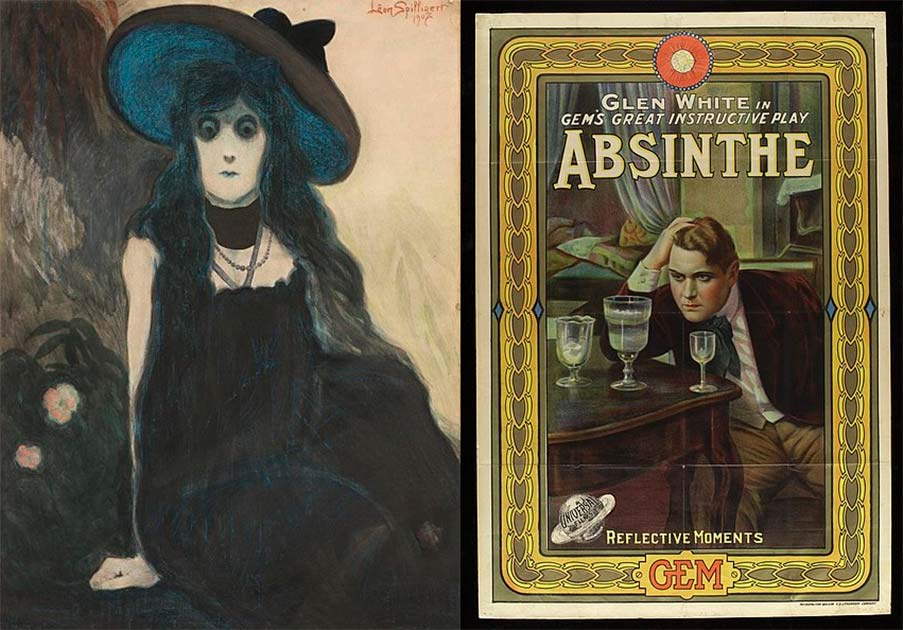

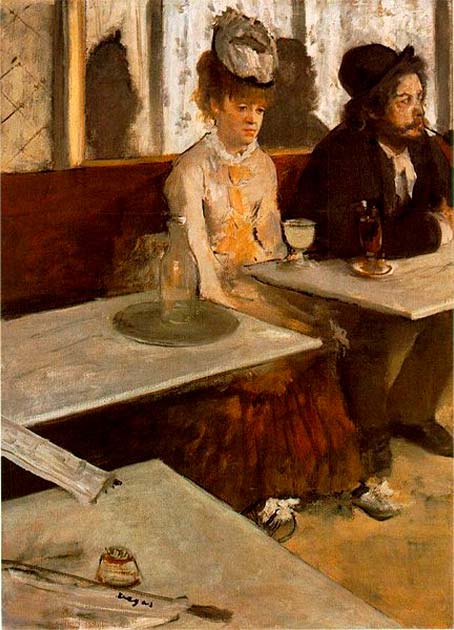

In literature, absinthe is often referred to as la fée verte, aka “the green fairy,” It became prevalent in France in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Absinthe was the preferred drink of artists and writers and was associated with bohemian culture.

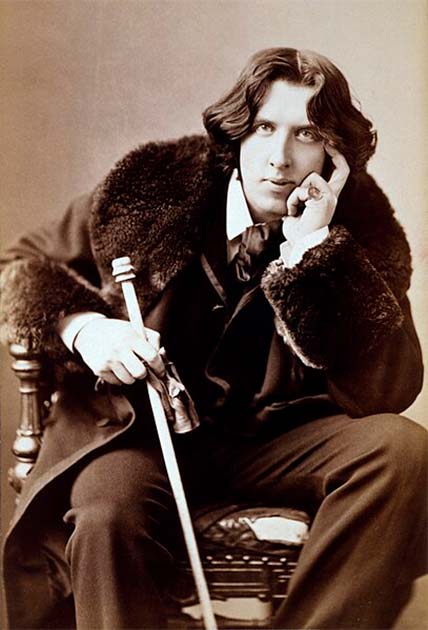

Social conservatives and prohibitionists loudly opposed the sale and consumption of absinthe because of its ties to this lifestyle, which they saw as decadent and corrupted. Some famous absinthe drinkers from history include Ernest Hemingway, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Edgar Allan Poe, Vincent van Gogh, Oscar Wilde, Aleister Crowley, Lord Byron, James Joyce, Picasso, and Lewis Carroll.

The exact origin of absinthe is unclear, but wormwood, where the spirit gets its name from, has been used for medicinal purposes stretching as far back as ancient Egypt’s Ebers Papyrus and ancient Greece. Wormwood leaves were usually soaked in wine or other spirits and were said to be used to help women during childbirth.

The father of medicine, Hippocrates, would give wormwood to patients with anemia, rheumatism, jaundice, and menstrual pain. Of course, Pliny the Elder wrote about using absinthe in his Natural History. Pliny describes winners of chariot races drinking absinthium to symbolize and remind the champions that “glory has its bitter side.”

While absinthe, the drink as we know it today, is often associated with France, the spirit originated in the canton of Neuchâtel in Switzerland towards the end of the 18th century. As absinthe grew in popularity, it was given to French troops to prevent malaria infections (entirely in error, and it is worth noting it can not prevent nor treat malaria).

- The Flesh of a God: In Search of a Mystical Mushroom

- Toxic Leadership: Did the US Govt Poison Prohibition Alcohol?

When soldiers returned home, they brought their taste for absinthe with them. What was unique was that absinthe was drunk across all social classes in France, from the bourgeoisie to the working class. By 1910, the French were said to have consumed 36 million liters (38 million quarts) of absinthe which is a significant amount, although still dwarfed by the country’s annual consumption of 5 billion liters (5.3 billion quarts) of wine.

Mind-Altering Powers

Absinthe was popular among artists, writers, and other creatives because it had an alleged history of causing hallucinogenic effects. Although creativity takes courage, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a glass of green liquid courage could stimulate creative minds to produce masterpieces.

The way absinthe was touted as a tool for altering perceptions only added to the mythos of absinthe. For example, Oscar Wilde said, “A glass of absinthe is as poetical as anything in the world. What difference is there between a glass of absinthe and a sunset?”

Another absinthe drinker Ernest Hemingway described the spirit as “idea-changing liquid alchemy” and “It’s supposed to rot your brain out, but I don’t believe it. It only changes the ideas.” But then Hemingway said a lot of things.

Along with hallucinations, absinthe became associated with things including mania, violence, erratic behavior, and psychosis. Those opposed to intoxication or the production/sale of alcohol, politicians, and medical professionals were quite vocal about the dangers of absinthe.

In France, one critic stated that “Absinthe makes you crazy and criminal, provokes epilepsy and tuberculosis, and has killed thousands of French people. It makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, it disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country.”

What led to widespread bans on absinthe was a tragic event known as the “Absinthe Murder” in 1905. Swiss man Jean Lanfray shot and killed his pregnant wife and two and four-year-old daughters after consuming two glasses of absinthe before falling unconscious.

When he came to, Lanfray was unaware that his family was dead or that he was the one to kill them. He had no recollection of the previous night’s activities and was in disbelief at what he was alleged to have done.

That was how powerful absinthe madness was; an entire family was killed due to absinthe. It should be noted that Lanfray was an alcoholic and had been drinking heavily throughout the day before he killed his family.

The anti-absinthe movement had been mild across Europe, but when the absinthe murders occurred, widespread bans on the spirit spread across the world at a startlingly rapid pace. Brazil and Belgium saw the green fairy banned in 1906, and by 1908, Switzerland added anti-absinthe legislation to their constitution. Further bans occurred in the Netherlands in 1909, the United States in 1912, and finally even France in 1914.

The Truth About Thujone

The chemical compound thujone was thought to be the cause of absinthe madness and hallucinations. Thujone is a natural and toxic compound that exists in the species of wormwood that is used to produce absinthe.

Thujone is a GABA (Gamma-aminobutyric acid) inhibitor and blocks GABA receptors in the brain, which can lead to convulsions and seizures if enough thujone is consumed. While this sounds damning, the truth is, a bottle of absinthe does not have enough thujone in it to harm anyone.

Studies were performed on absinthe, thujone, and its effects on humans. The conclusion was that thujone would only impact someone’s mood and physical performance if consumed in very high volumes.

Thujone is present in many of the foods we eat, but the doses of the toxin are never enough to harm you. When it comes to absinthe, the distillation process results in a very small amount of thujone per bottle.

In the US, only 10 milligrams per liter is permitted in absinthe, while in Europe, absinthe may have around 35 milligrams per liter due to different food and alcohol laws per country. Scientists found that a “person drinking absinthe would die from alcohol poisoning long before he or she were affected by the thujone. And there is no evidence that thujone can cause hallucinations, even in high doses.”

When absinthe samples were tested from old, sealed bottles in the US, France, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, and the Netherlands that were bottled in the early 1900s prior to bans on the spirit, researchers found that the amount of thujone in those samples was minimal. The amount of thujone from the samples was about the same amount found in modern absinthe.

It is believed that the claims by artists and authors of altered states of perception were caused by the alcohol in the drink. Absinthe today has a high level of alcohol by volume, even with government limits on how much alcohol can be sold and served. The absinthe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries likely contained insanely high levels of alcohol.

Absinthe is never drunk straight; it was (and still is) diluted with water before consumption. Even if a glass was diluted with water back then, the alcohol content was so ridiculously high that the drinkers would get drunk.

Those who drank absinthe did so in large quantities, and the reported effects of absinthe are the same as those caused by alcohol intoxication. Effects like self-confidence, excitement, and euphoria were reported.

We now know today that alcohol impacts the way the brain can communicate. Alcohol makes it harder for your brain to control your balance, manage emotional stability (why some people get sad or mad when drunk), speak clearly, impact vision, and can make you drowsy.

Many artists and writers who praised absinthe’s ability to alter the mind were consuming other mind-altering substances and large amounts of alcohol. Ernest Hemingway was a heavy drinker, as was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Edgar Allan Poe used opium, and his body could not process alcohol, and although it made him incredibly ill, he still drank large quantities of alcohol. Van Gogh was a heavy drinker, was mentally ill (prone to hallucinations), and is believed to have been exposed to dangerous chemicals from his paints. Oscar Wilde was notorious for his love of absinthe and opium.

Opium was also popular with Picasso and Lord Byron. Crowley openly spoke about his use of mind-altering substances, and James Joyce was addicted to cocaine, morphine, and inhalants.

While many people claim that Alice in Wonderland is all about drugs, Lewis Carroll was a drinkers but not a regular drug user. He did however use laudanum which was prescribed for everything from pain to helping babies sleep.

Both Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and James Joyce also had syphilis which causes depression, mania, delirium, and psychosis. On top of the disease’s impacts on the brain, mercury was used to treat the condition until penicillin in 1928. These things aren’t often included in the myths of absinthe and the green fairy, which allows the idea of its ability to alter the mind to persist.

Top Image: The Green fairy visits: The Absinthe Drinker by Viktor Oliva. Source: Viktor Oliva / Public Domain.