In the south east of Tanzania, in southern Africa’s east coast, lies an intriguing archaeological oddity. Located on a coastal island is the settlement of Songo Mnara, and archaeologists hope that this town, and others like it, will show how African Swahili coast interacted with Islam.

The small island located on the southern coast of Tanzania was occupied from the 13th to the 16th century. Deserted now, it was once clearly a successful and prosperous place.

Along with the island of Kilwa Kisiwani, Songo Mnara served as an important point in the coastal Swahili culture and Indian Ocean trade. Both the ports served as a channel for trading in timber, jewelry, ivory, clothes, pearls, porcelain and gold.

Both islands grew wealthy from such trade, as the stone structures they built attest. Let us find out some more details about the East African port island in Tanzania and how Islam was spread among the Swahili.

Swahili Culture

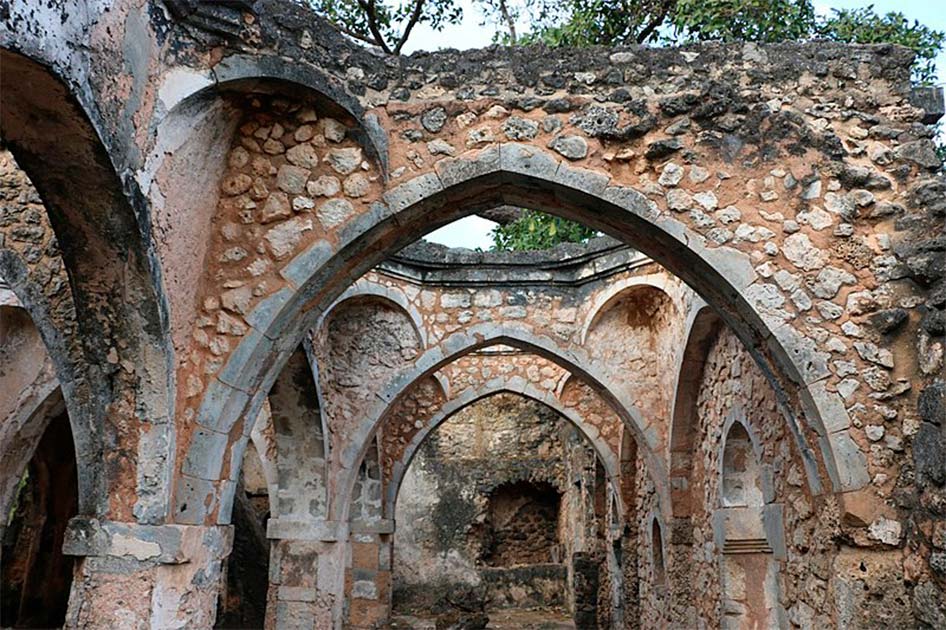

Songo Mnara is one of the two prominent East African ports which had gained the attention of early European explorers. Located on a small island near the coast in the Kilwa District of Tanzania, Songo Mnara houses a stone town built in accordance with medieval Swahili culture. The stone town had been occupied from the 14th to 16th century with archaeological evidence of elegant architecture enduring.

Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of four cemeteries, twelve house blocks, three enclosed “paddocks” of land and six mosques. The materials used in the construction of the stone town are rough coral and mortar.

The primary use of Songo Mnara as a port belies its focus: African traders must have built the town, and they were looking outwards to the oceans. It is one of the many trade cities lining the Indian Ocean, and the architecture of the town suggests that the place had a prominent role in the growth of Swahili culture.

- Africa’s Strange Ruin: What Exactly Is Great Zimbabwe?

- Who Built the Temples of Malden Island, and Where did they Go?

The design of the town and its role in placing the East African coast on the world trade map indicates that the town must have been under the influence of wealthy merchants. Along with the island of Kilwa Kisiwani, Songo Mnara stands as a witness to the flourishing Indian Ocean trade across a massive region.

It served as an important port in one of the formidable trade routes from the medieval era to the modern period. The stone town on the island has housed significant evidence for describing another chapter of world history.

Why was it Abandoned, and where did the People Go?

The two islands of Kilwa Kisiwani and Songo Mnara have offered a wide range of opportunities for archaeologists to uncover evidence about the development of trade, politics and social dynamics. The design of the stone town primarily focused on establishing a connection between the mosques and houses.

Songo Mnara has a similar design to many other stone towns across the Swahili coast. However, it has a unique feature in the form of its town walls: apparently there was a need for a strong defense.

Songo Mnara is in ruins now, but there is much it can tell us. The archaeological evidence of a palace, domestic dwellings and mosques show that the people of the region had developed an organized community. The nearby island, Kilwa Kisiwani, also offers more evidence for the quality of life in the stone towns.

Within the ruins of Kilwa Kisiwani, archaeologists have discovered evidence of what has been dubbed the “Great Mosque”. From a core 11th century building, the structure was expanded further in the 13th century.

The detailing in the design of the roof, along with the use of embedded Chinese porcelain, proves the effectiveness of architectural design in the region. In addition, the island also had a massive octagonal bathing pool, a prison, burial grounds, and multiple mosques.

The reasons for which people abandoned Songo Mnara and Kilwa Kisiwani are yet unknown. One of the common explanations for people hastily abandoning the stone towns points to the arrival of the Portuguese on the Indian Ocean trade route.

A Melding of Cultures

The archaeological excavations in Songo Mnara have offered new and surprising insights into the Swahili culture in the region. Differences in the designs of Swahili towns across the region and rarities, such as the walls in Songo Mnara, reflect the complexity of understanding Swahili architecture.

- Who Built the Abandoned City of Djado? A Saharan Mystery

- Who Built the My Son Sanctuary, and What did they Believe?

In addition, the prevailing colonial occupation of the region for 500 years resulted in coalescing of Swahili cultures with colonialist cultures. Certainly, nothing is being built like these stone towns now.

The functionality of an architectural design practiced two centuries ago seems impractical now. At the same time, some could also point to the problem of sustainability in building stone towns, which require significant investments of resources and manpower.

The growth of Kilwa Island showed how it started from a mere group of stone structures to a massive stone city in the 15th century. Songo Mnara may have developed faster and seems to have had an urban plan from the start, but it is not clear whether this is the case, or whether the arrival of Islam changed things.

The difficulty in building such towns is the need for powdering and plastering coral blocks with coral lime. The coral was derived from live Porites coral only when fresh. Hence, you can understand why it is difficult to build stone towns like the ones in Songo Mnara and Kilwa.

However, at the time the Swahili considered it to be worthwhile. Both the islands served as crucial ports in the Indian Ocean trade routes and developed significantly into large population centers.

One of the notable highlights of the design of Songo Mnara stone town is the use of an urban plan for creating the town. It seems that Islam was absorbed into this plan, but the design was Swahili and the town was, too.

Top Image: A town built of coral: the central building of Songo Mnara. Source: Ron Van Oers / CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO.

By Bipin Dimri