Whitechapel is one of the oldest districts of London. Hard by the old City of London with the towering glass skyscrapers of the business and financial district, it is a maze of roads, parks and old buildings. Today it is perhaps best known for being the area Jack the Ripper prowled, murdering prostitutes amid the dark alleyways.

Much of the old Whitechapel has been lost to urban redevelopment in the century since the Ripper, but some of the old character survives. The churches still stand, dwarfed by the buildings that surround them. Pubs and parks are somewhat as they used to be, and behind Liverpool St Station there are still a few alleyways of Victorian London, now home to karaoke and wine bars.

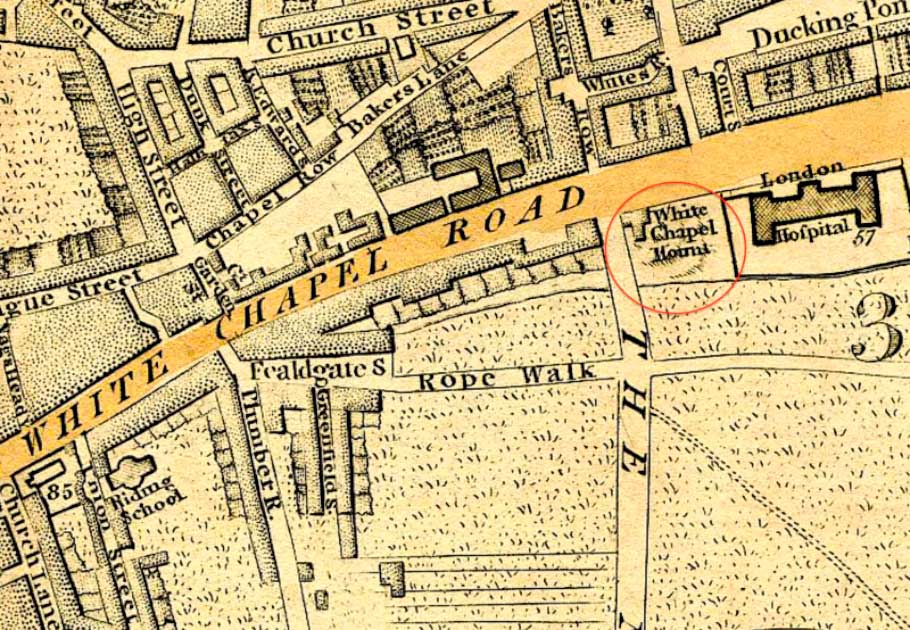

But perhaps the most significant feature of Whitechapel is one that most Londoners are not even aware of. A century before Jack the Ripper, in the 1700s, there was Whitechapel Mount, a huge mound taller than the nearby newly-built London Hospital. This great hill, although completely gone now, once dominated the surrounding landscape.

And nobody knows what it was.

The Origins of Whitechapel Mount

The origins of the Whitechapel Mount are still disputed, and there are many theories about how it came to be there, dominating one of the main roads into the old City. Historians believed that the mound was artificial, maybe a defensive structure erected in bygone times to guard London’s eastern approach.

Even the great London Hospital, built nearby, was dwarfed by the great mound. Fully 400 yards (366 meters) long, it stood amidst the fields and houses, a part of the landscape clearly visible in many paintings until the early 1800s.

We do know what happened to the Mount: records show it was levelled to the ground in 1807 to make way for new, more modern constructions. We also know why Whitechapel Mount was levelled, as Londoners of that time believed that the detritus from the Great Fire of 1666 had been collected into a huge pile of rubble. Looters and opportunists would scour the mount, looking for valuables.

However, this was only a theory and there is no evidence that this is what happened. Much of the London destroyed by the fire was constructed of wood and plaster, and the remains could not have formed such a towering mound. Similarly, nothing of value has ever been conclusively proven to come from the Mount.

A Key Location?

Whitechapel Mount was situated at the south end of Whitechapel Road, an age-old route between the City of London and the port of Harwich, running through such ancient towns as Colchester and in use since before the Romans invaded millennia ago.

Before it was levelled during the 19th century, the route was surrounded by fields and grazing pastures, dotted with trees and small houses. In fact, given its location and height, in the daytime Whitechapel Mount served as a scenic high point for visitors who wanted to get a bird’s eye view of the old walled City.

The Mount was much more dangerous after dark, however, becoming a den of scoundrels and thieves who used it as a hiding place and stashing point for stolen goods. The Mount was also crossed with tracks and walking roads for travellers and visitors. People could even go up and down the Mount with the help of horse carts and mules.

What the Whitechapel Mount was, in reality, is still not clear. Some people think that it is almost as old as the City itself, raised by the early Saxons as a defensive structure similar to other great earthwork fortifications in the south of England.

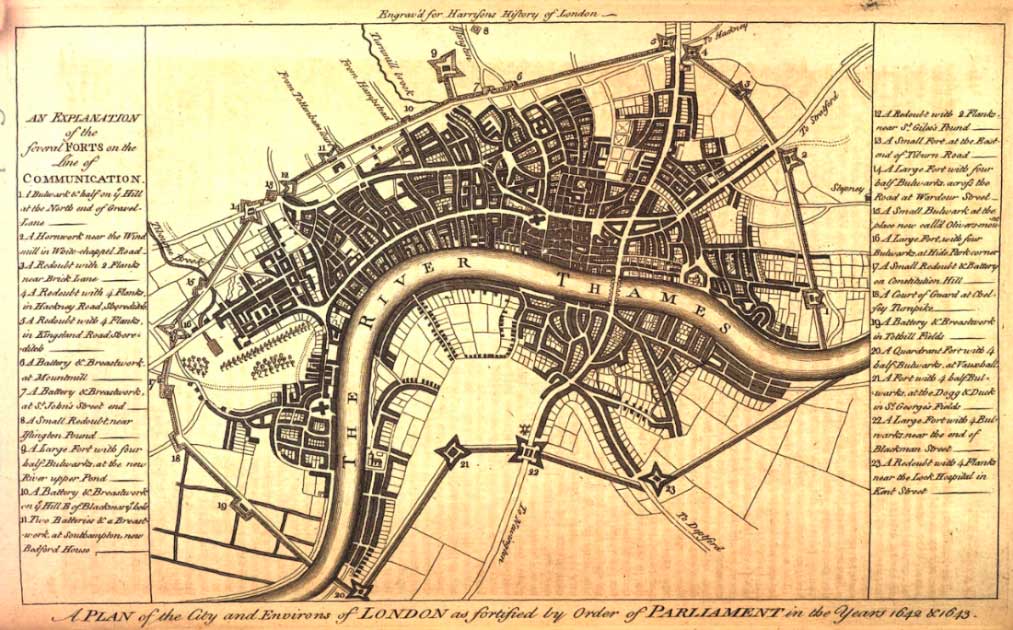

Others think that it was a defensive structure dating back to the English Civil War, when the Parliamentarians of London faced off against the Cavalier royalist forces of Charles I in the 17th century. Some theories even pitch the idea that the Mount was the burial place of those who died in the Great Plague of 1665.

On the other hand, some people believe that it was the burial place of the victims of the Great Fire, which happened the following year – London was clearly particularly cursed at that point in history. Some people also believed that the Whitechapel Mount was nothing more than a huge pile of cattle dung, as cattle driven to market were often corralled in the area before sale. The Mount was also called Whitechapel Dungshill, which would seem to support this theory.

In truth, the entire area in the 17th and 18th centuries would have been largely rural. Houses and travelling inns were few and scattered compared to today, surrounding the old St Mary Matfelon Church, a windmill, a ducking pond (a pond to duck criminals in, not a pond containing ducks) and a burial ground. The latter is perhaps the reason the Mount itself was thought to be a burial ground, although they are clearly separate.

What Can History Tell Us?

Records of the Mount most commonly refer to its’ associations with brigands. The Whitechapel road was very busy and commonly full of highwaymen and bandits who stole from travelers and heckled them while they were either on their way to London or coming from it. Since the Mount was a good hiding place, it offered an advantage and a great hiding place for such riff-raff.

Many court reports dating back to when the Mount existed to talk about murders and robberies being common near the Whitechapel Mount. The Mount was infamous, a possible factor in the decision to level the area and allow urban development.

The earliest maps which clearly contain the Mount date from the 1600s and 1700s, where the location is always clearly marked. Interestingly the Mount is sometimes referred to as “The Fort” and described as a mud wall. From this, it is clear that historians and local people believed it to be a defensive structure erected for protection, and some surviving descriptions even refer to the Mount as a timber castle of sorts, although there seems to be no corroborating evidence for this.

However, the human activities that happened around the Mount in Industrial Era London garnered its later identity, and new theories started revolving around it. In some maps, the Mount is referred to as a Dunghill and perhaps it grew with the cattle effluvia over the years as more and more cows were brought to market. Such great piles of rubbish and dung certainly existed, a key feature for example in the Victorian novelist Charles Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend.

Whether the Mount was a fortified wall or a burial ground for unfortunate souls, it was once a part of the vast London landscape. There are many stories linked with the Whitechapel Mount that historians and history enthusiasts talk about even today.

But today all we have are theories. Eventually, the Mount was levelled with the plans of London’s new constructions expanding London’s docklands. After levelling the ground, the streets of Mount Terrace and Mount Place are all that remain to reference this great, strange, unexplained feature of the ancient City.

Top Image: Whitechapel Mount, six years before it was levelled The new hospital can be seen to the left of the picture. Source: Unknown Author / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri