The Franklin Expedition

In 1845, two ships named the Erebus and the Terror set sail into the Canadian Arctic. Neither returned home, and 129 members of the expedition and both ships were lost. The journey itself has been shrouded in mystery as few logs survived and there were no survivors to tell the tale. Even the purpose of the journey has caused confusion. Recent scientific advancements, however, have begun to unravel some of the secrets of this journey and to reveal what really happened to some of the long-lost crew.

Origins of the Expedition

At the start of the 16th century, the world was obsessed with exploration. Inspired by the discovery of the “New World” by Christopher Columbus in 1492, European powers began to push the boundaries of their borders, which included exploring the Arctic and Antarctic.

However, this truly began to dominate British politics in the 1800s. By the 1820s polar exploration was hugely popular, with one of the greatest prizes being the discovery of the infamous “North-West Passage” and a navigable northern route connecting the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans.

The Expedition Leaders

The commanders chosen for this trip were not the first choice. Despite both being veterans of naval expeditions, John Franklin and Francis Crozier were only chosen after the proposal was rejected by the preferred choices of James Clark Ross and William Edward Parry. However, Franklin and Crozier should not be viewed as poor choices for command:

Sir John Franklin was the overall leader and namesake of the Expedition, and an experienced naval commander. He had joined the Royal Navy at age 14 and served in the battles of Trafalgar and New Orleans. In addition to this, he took part in an expedition to the North Pole in 1818, and conducted an overland expedition from Hudson Bay to the Arctic Ocean and North-western Canada. Ultimately, his experience and qualifications were considered sufficient to lead this crucial journey in 1845, commanding the mighty Erebus.

Second in command to Franklin, Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier joined the Royal Navy at age 13 in 1810. He spent just over a decade sailing around the Pacific, eventually rising to the rank of ship’s mate in 1817. In 1821, Crozier was appointed to William Edward Parry’s Arctic expedition to find the Northwest passage, and would continue to return to the Arctic over the following years.

It was during this time that he also befriended James Clark Ross. He was a well-experienced Lieutenant and even gained a Fellowship at the Royal Astronomical Society for his work in magnetic studies. Clearly, this expedition was not poorly led.

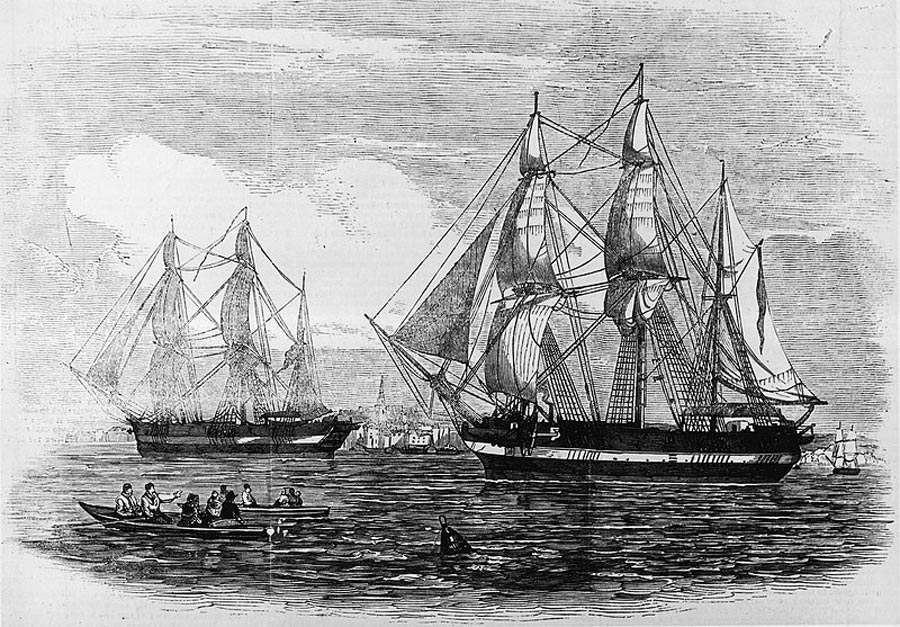

The Erebus and the Terror

Both ships used on this expedition were repurposed warships. This means that they were extremely well built and hardy.

Built in June 1813, Terror was a “bomb vessel” built to withstand huge explosions and impacts. She first saw action in the War of 1812 against the United States. Surviving many a foray into battle, she was selected for the 1845 naval expedition.

Built later in 1826, Erebus was also a warship. However, in addition to her career in military affairs, Erebus also had a long and proven history in Polar exploration, under James Clark Ross between 1840-1843.

Before the expedition, both ships were completely refitted with an additional strengthening of the hull and an internal heating system. Further planking was refitted on the upper deck and iron sheeting was added to the side of the bows. Finally, steam engines and propellers were added to aid in navigation. They were as well prepared as any ship could hope to be.

The Expedition

Setting off in 1845, the two ships left England and begin their long journey to where they believed they would find the Northwest Passage. The vessels were last sighted near Baffin Island in North-eastern Canada, but then were not heard of for over two years. Various rescue missions were put together, but no news arrived until 1859, when Francis Leopold McClintock reached King William Island, some 750 miles (1,200km) to the Northwest. There he found multiple skeletons and an account of the expedition.

According to this account, the two ships had become entrenched in ice in 1846, a year after setting off. Franklin had hoped they would be able to break free but by 1848, he was dead along with 23 of his men. Crozier decided to abandon the ship with the remaining crew and attempted to head south to North America.

A local Eskimo woman revealed how the crew had resorted to cannibalism in their desperation, and were dying of exhaustion. More recently, parts of the ships have been found in 2014 and 2016 that showed much of the hulls intact. However, little else was able to be discovered from the wreckages.

DNA Sheds Light on the Tragedy

That was of course until recently when a member of the crew from 1845 was identified by researchers using DNA. Tests conducted on the skeletal remains concluded that one of the skeletons belonged to John Gregory, an officer of the expedition. Using bone and tooth samples, scientists were able to trace a link to Gregory’s great-great-great grandson, Jonathon Gregory.

The research has not only provided the family with closure, but revealed more about life on the voyage. John Gregory spent 3 years trapped inside HMS Erebus before disembarking under Crozier’s command. He managed to travel 75km south, but ultimately died in Erebus Bay, likely through starvation, exhaustion, and even potential lead poisoning from the tinned food they had been eating.

John Gregory was the first member of the expedition that has been positively identified through DNA testing. The testing itself has provided huge insights into the lives of those on the ships as well as information on their age, stature, and overall health on the voyage. What is more remarkable than anything else is that despite the horrific conditions in which the crew found themselves, they were able to live for three years trapped in the ice. This is a telling testament to how well prepared both ships were for the coming expedition. Ultimately, however, it would have taken a miracle for the crews to survive.

Top Image: The Erebus. Source: Richard Brydges Beechey /Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri