The Cold War was a conflict like no other. A quiet, hidden conflict, drawn out and defined by intelligence collection, propaganda, and the race for nuclear weapons. This was a war won and lost by spies and by betrayal.

And of the all the treasonous betrayals, none was perhaps so severe, and had such far-reaching consequences, as that of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. How did the Rosenbergs get their hands on such vital intelligence that the government was obligated to rewrite tradition?

And did they deserve to die?

A Web of Spies

Ethel Greenglass was born in 1915 in New York and grew up in a traditional family. Julius Rosenberg, likewise, was born in New York in 1918. Julius and Ethel showed dissatisfaction with their country’s politics from an early age, becoming members of the Young Communist League while in university in the early 1930s. Following that, the two became involved with the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), and this is where they met and fell in love.

In 1939, the couple married two children quickly followed. Ethel was a clerk, and Julius had joined the US Army Signal Corps as a civilian engineer, thus the Rosenbergs set out to pursue seemingly normal jobs. Julius left the CPUSA just before commencing his career with the US army to avoid being accused of communist sympathies.

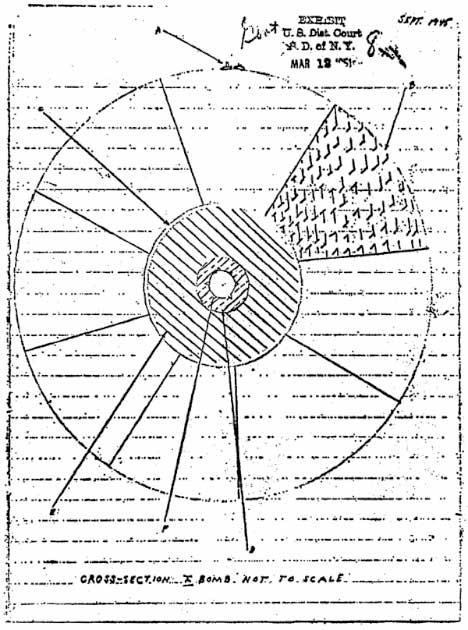

Sergeant David Greenglass, Ethel’s brother, worked for the Manhattan Project in New Mexico, a group tasked with developing the world’s first atomic bomb. Greenglass had access to radar, sonar, and jet propulsion engine technology, as well as other important nuclear weapon designs.

He was actively involved in the bomb-making process and was a huge benefit to Julius, who wanted to give the Soviets as much nuclear information as possible. Julius, whose communist beliefs had never died and who had been steadily developing a network of spies, saw having a brother-in-law working at the Manhattan Project as a great asset.

Julius had recruited aviation experts, machinists, and engineers into his spy network, all of whom had access to material considered classified for national security reasons. The information was subsequently passed on to Harry Gold, who had been active in the communist cause since its inception.

Harry Gold was more than just a handler, however. He’d worked his way up at the Manhattan Project to become a laboratory chemist. Gold was Rosenberg’s go-between between the Manhattan Project and the USSR.

- Project Azorian: Did Howard Hughes Try to Steal a Russian Sub?

- Traitors To The Crown: Who Were The Cambridge 5?

From the first, it wasn’t all about the money. Julius Rosenberg was once compensated $500 for crucial information he gave regarding an atomic bomb’s implosion lens, a significant amount at the time. However it seemed that it was his beliefs that led him to give up secrets to the Soviets, secrets which allowed them to build their own bomb.

But in 1946 Julius was discharged from his employment after it was discovered that he had lied about his communist party membership. But by then the damage was done, and it seemed that the couple’s spying activities had gone unnoticed.

It All Comes Crashing Down

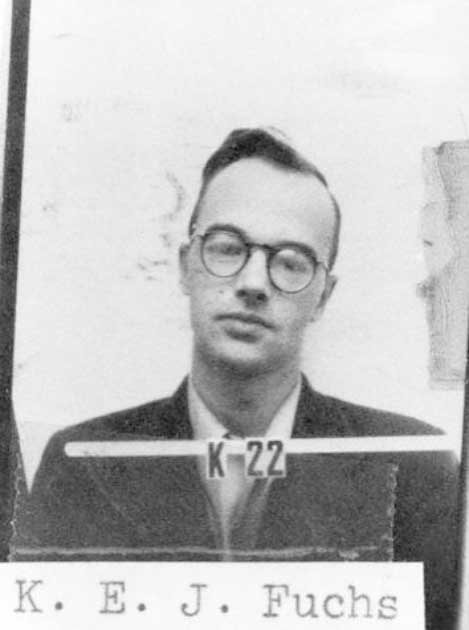

Soviet coded messages were deciphered by the US Army Signal Intelligence Service in 1949. They discovered a name in one of the decrypted documents codenamed The Venona Project: Klaus Fuchs.

Fuchs was working as a physicist at Los Alamos University at the time. The documents revealed that the British physicist had been operating as a spy, sending British and US secrets to the Soviets. Fuchs was apprehended in the United Kingdom immediately, and unfortunately for many other spies, he divulged a list of other members of his espionage ring.

This created a ripple effect that resulted in the arrests of a slew of further Soviet spies. Gold and Greenglass were among the names Fuchs revealed. The FBI was desperate to find the ringleaders swiftly, and it’s suspected that they put a lot of pressure on Greenglass. For fear of the arrest of his wife, Greenglass gave up the names Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

On July 17, 1950, Julius was arrested for conspiracy to commit espionage, one month later Ethel was arrested for the same crime. Their trial lasted for only a single month, beginning on March 6, 1951, and concluding on April 5, 1951. The evidence of David Greenglass was one of the most important factors in their conviction, with Greenglass receiving only ten years in prison for the information he divulged.

The pair continuously asserted their innocence and pleaded the fifth (amendment, the right to avoid self-incrimination) during the trial. But it was all for naught and on March 29, 1951, the court judged Julius and Ethel Rosenberg guilty of conspiracy to commit espionage and sentenced them to death. The couple were executed by electric chair on June 19 1953.

Judge Kaufman spoke about his decision to choose to use the death penalty, “I consider your crimes worse than murder. I believe your conduct in putting into the hands of the Russians the A-bomb years before our best scientists predicted Russia would perfect the bomb has already caused, in my opinion, the Communist aggression in Korea, with the resultant casualties exceeding fifty thousand and who knows how many millions more of innocent people may pay the price of your treason.”

Was Justice Served?

This decision made them the first civilians to be sentenced to death for espionage during peace times. The draconian application of the death penalty divided public opinion in the United States, as many of the details relating to the crime and the conviction remained secret.

- UK Prime Minister Turned Traitor: Was Harold Wilson a Communist Spy?

- Operation Northwoods: A US Terror Campaign Against Itself?

Some believed the brutal punishment was a government tactic intended to make an example of anyone who dared to defy the US government. It wasn’t until years later in 1995 when the previously classified Venona Project documents were released both questions were answered and created.

The pseudonym “Antenna” featured frequently in these documents; it was the codename given to Julius by the Soviets. According to the decoded documents, Julius had been a high-ranking spy who utilized his connections in the Manhattan Project to convey secrets to the USSR’s industrial and military sectors.

When it came to Ethel, her involvement seemed to be a little different. Her name appeared in the documents, but not as a codename, indicating that she was not a spy but may have had ties to one.

If these documents had been made public during the trial, it would have raised doubts about Ethel’s guilt. Many people assume Ethel was arrested to persuade Julius to disclose the identities of other spies operating against the United States.

The original statement made by David Greenglass before Rosenberg’s trial adds to the argument for Ethel’s innocence. Greenglass asserted, “I said before, and say it again, honestly, this is a fact: I never spoke to my sister about this at all”. In reality, if these papers had been made public during the trial, the Soviets would have known that their code had been cracked, and the US would have lost its advantage.

But, just ten days before the trial, Greenglass changed his testimony, which was critical in Ethel’s conviction considering her involvement was unclear at the time. Greenglass later indicated to a New York Times journalist that he had made a deal with the government that if he identified his sister was involved, they would give his wife amnesty.

Too Late To Keep The Secret

Although it is impossible to completely grasp the significance of Julius and Ethel’s espionage today, some feel that the knowledge they provided spurred the Soviets forward in the race to develop the atomic weapon. One thing that came out of this trial was the government’s apparent willingness to go to any length to appear strong in the eyes of its adversaries. Even if it meant killing a citizen with little to no evidence.

Former US President Dwight D. Eisenhower stated, “I can only say that, by immeasurably increasing the chances of atomic war, the Rosenbergs may have condemned to death tens of millions of innocent people all over the world. The execution of two human beings is a grave matter. But even graver is the thought of the millions of dead whose deaths may be directly attributable to what these spies have done.”

President Eisenhower seemed to characterize Julius and Ethel Rosenberg’s treasonous betrayal in his condemnation, but it is still uncertain what impact their treasonous betrayal had on the outcome of the Cold War. What is evident is that the US government was willing to conceal information and break laws to defend their country’s security.

Top Image: Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were executed for giving the Soviets the secrets to building an atomic weapon. Source: Roger Higgins / Public Domain.

By Roisin Everard